The Issue: At its mid-June FOMC meeting, the Fed announced that it was holding its target for the federal funds rate unchanged at 5 to 5-1/4 percent following ten consecutive increases that accumulated to 5 percentage points. The Fed reasoned that it wanted time to assess the impact of previous rate increases and the extent to which restraint by lenders prompted by disturbances to the banking system in the spring was slowing the economy and moderating inflation. Chair Powell has since conveyed that the mid-June decision was a pause and that the Fed is disposed toward additional rate hikes in coming meetings. Does recent evidence indicate that the Fed’s job of slowing the economy to curb inflation requires further rate hikes or is the task nearly finished?

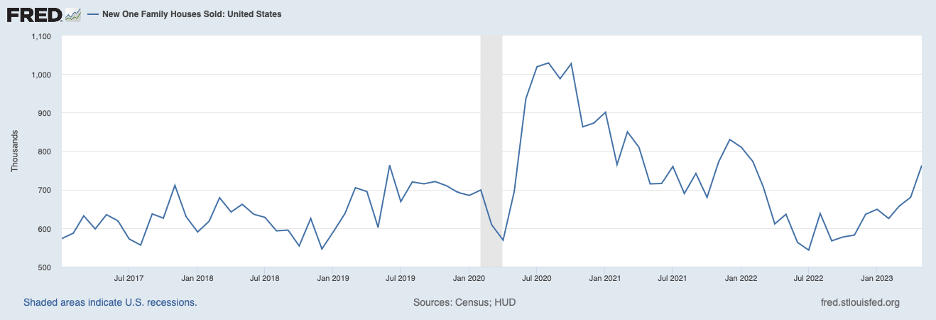

The evidence: One indication that the Fed’s job is not close to being finished can be found in the housing sector. Historically, housing has been among the most responsive sectors of the economy to monetary policy actions—throttling down when the Fed is tightening and swinging up when the Fed is easing. The chart below, showing sales of new homes, illustrates that new home sales dipped in the wake of the onset of Fed tightening in 2022 but have turned up over recent months to reach a level in excess of the pre-COVID period. Looking ahead, the housing sector will need to slow from its recent pace to perform its typical role in relieving pressure on resources and inflation. (Existing home sales have displayed a somewhat similar pattern to new home sales, but the upturn recently has been less pronounced reportedly because of the low inventory of existing homes available for sale.)

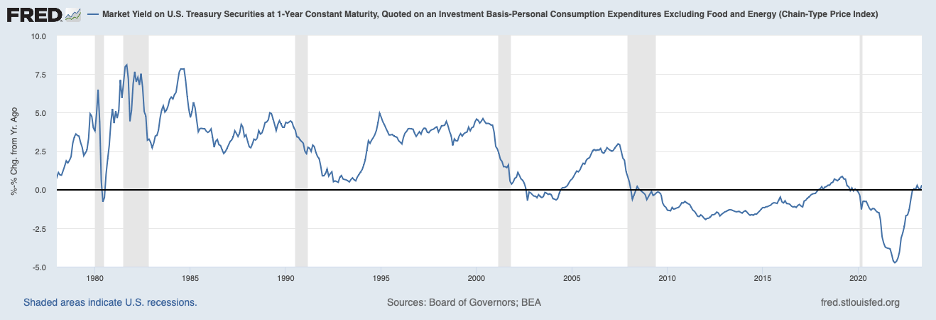

Further evidence that the Fed’s tightening job is far from over comes from the real one-year Treasury bill rate, is shown next. The chart plots the nominal one-year Treasury bill rate less the twelve-month increase in core PCE inflation through May (most recent data on core PCE inflation). The real bill rate has been barely above zero recently and roughly one percentage point below the estimated neutral level at which monetary policy is neither expansionary nor contractionary. To begin to apply restraint on underlying inflation, the real bill rate likely will need to increase more than one percentage point. Consequently, the Fed will need to raise the federal funds rate by this amount (or perhaps by more because the nominal bill rate in May already had expectations of another ¼ percentage point increase in the federal funds rate built in). Note that even if the real bill rate does move one percentage point higher, it will still be well below levels in the early 1980s when the Fed was waging a tougher war against inflation. (It is worth noting that the neutral rate in the early 1980s is estimated to be on the order of 2 percentage points higher than it is today and thus on these grounds the real bill rate would not need to reach as high as it got in the early 1980s to apply the same degree of monetary restraint.)

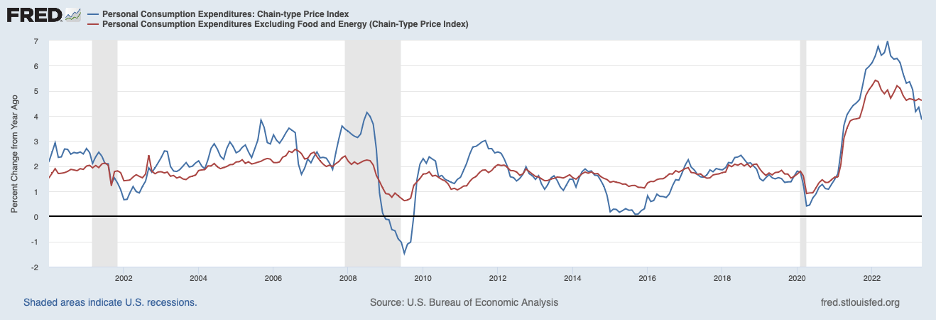

To date, the news on inflation does not point to relief. Shown in the chart below is headline PCE inflation (the blue line) and core PCE inflation (excluding volatile food and energy prices, the red line). The latter provides a better reading on underlying inflation. While headline inflation continues to recede, owing to declines in energy prices, core inflation has remained steady and well above the Fed’s 2 percent target.

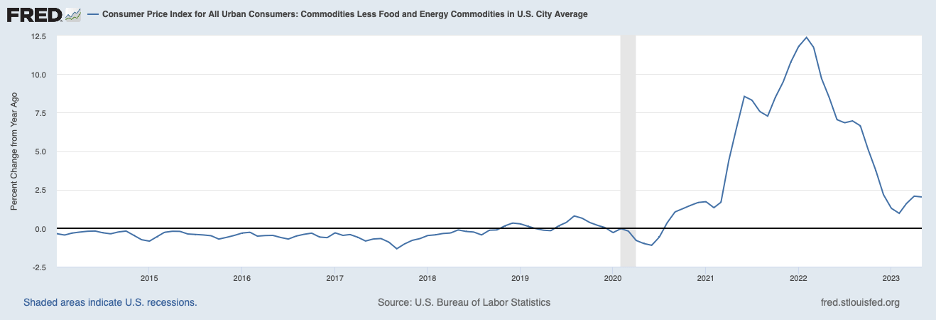

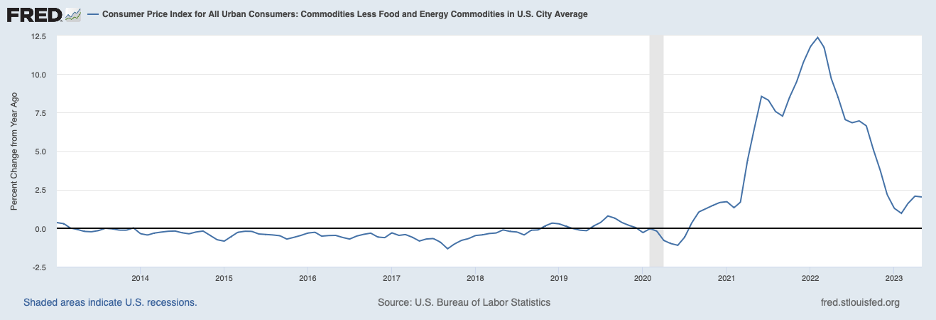

Moreover, it appears that the downward pull on headline and core measures of inflation coming from the impact of an easing of supply chain pressures on commodity prices has come to an end. The next chart shows that the dramatic drop in commodity price inflation (which excludes food and energy prices) has come to an end and commodity price inflation is outpacing pre-COVID rates by a sizable amount.

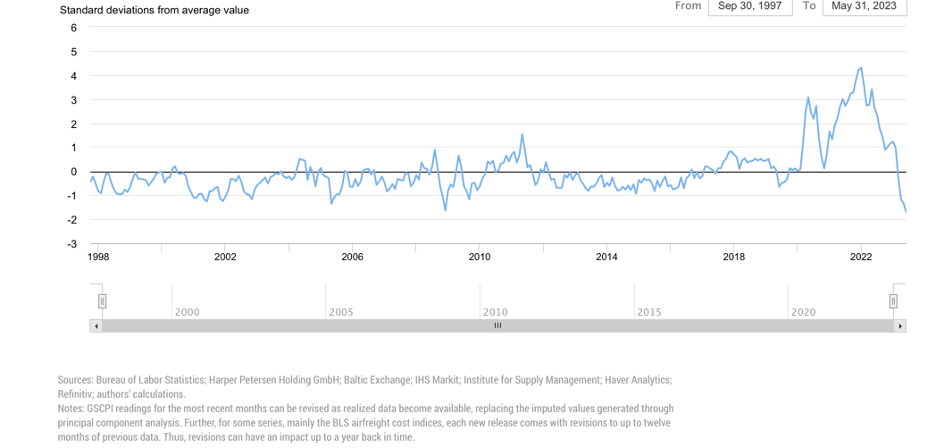

This upturn in commodity price inflation can be attributed to an unwinding of global supply chain pressures, shown in the next chart.

The intensification of supply chain pressures during the pandemic contributed to a surge in goods price inflation and the reversal of those pressures starting in the second half of 2022 acted to depress commodity price inflation.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

The implications: Recent evidence confirms that inflation remains entrenched and the Fed’s tightening to date has not been sufficient to place underlying inflation on a distinct downward trajectory toward the 2 percent target. History has shown that once inflation surpasses a threshold and remains there for a while, monetary policy needs to move well into the restrictive territory and remain in that territory for some time before the back of inflation can be broken. The implication is that the Fed will need to raise the federal funds rate a good bit more than one percentage point before we can feel comfortable that underlying inflation is moving onto a clear downward path.

Over the past couple of years, the Fed has been behind the curve, routinely underestimating inflation pressures and the level of the federal funds rate needed to place inflation on a downward trajectory. This recognition lag can be seen in the table below containing projections made by Fed policymakers for core inflation in 2023 and for the federal funds rate at year-end 2023. The table shows that over the past two years, the Fed has raised its projection of 2023 core inflation by nearly 2 percentage points and the year-end federal funds rate a full 5 percentage points. The most recent set of projections by the Fed envisions that the federal funds rate will top out a little above 5-1/2 percent, roughly ½ percentage points above the current level. The most recent set of projections also implies that core inflation in 2023 will slow markedly to 3.9 percent from 4.8 percent in 2022. To achieve the Fed’s projected 3.9 percent core inflation for 2023, the average monthly increase in prices over the remaining months of this year will need to slow to 0.28 percent from an average of 0.37 percent for the period to May. Under the conditions described above, such a moderation does not seem to be in the cards and thus more upward revisions to projected core inflation by the Fed in 2023 can be expected—and with it, upward revisions to the year-end federal funds rate.

FOMC Projections for Inflation in 2023 and the Year-end Federal Funds Rate

| Projection date | Median core inflation | Median federal funds rate |

| June 2023 | 3.9 percent | 5.6 percent |

| June 2022 | 2.6 percent | 3.8 percent |

| June 2021 | 2.1 percent | 0.6 percent |

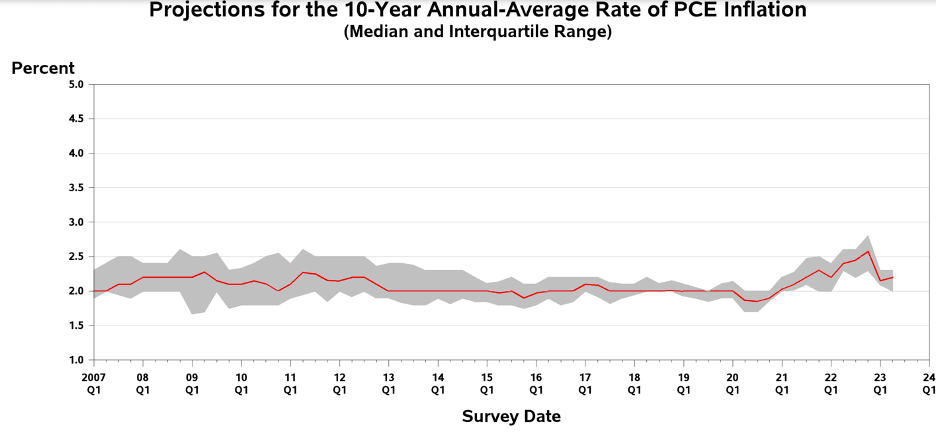

There is a silver lining in these clouds: The real interest rate will not need to rise as much as it did in the early 1980s to achieve victory in the battle against inflation. In part, this is because, as noted, the natural real rate of interest is now lower than in the early 1980s. Perhaps more important is expected inflation, especially longer-term expected inflation, which has not risen much above the Fed’s 2 percent target. Shown in the next chart is the median expectation for average inflation over the next ten years on the part of professional forecasters. Longer-term inflation expectations had drifted higher over 2021 and 2022 with actual inflation but retraced much of that increase over the first half of this year. Inflation expectations need to be anchored around the Fed’s 2 percent target for actual inflation to hold around a 2 percent rate and the chart shows that we are not far away from that point.

No doubt the relative stability of longer-term inflation expectations in the face of continued rapid actual inflation can be attributed to public statements by Chair Powell and other Fed officials about their commitment to the restoration of price stability as well as to the tightening actions taken to date. However, the longer that actual inflation stays elevated the greater the risk that inflation expectations will become unmoored and start to march upward. Should expected inflation turn higher, the Fed’s task of restoring price stability will become considerably more difficult. To avoid this outcome, the Fed should end the pause and finish the tightening job promptly.

Source: Survey of Professional Forecasters, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Nope never over got to get our money to pay for all those stupid things they come up with none of want or NEED ??????

Get Outlook for iOShttps://aka.ms/o0ukef ________________________________

LikeLike