Has the Back of Inflation Been Broken?

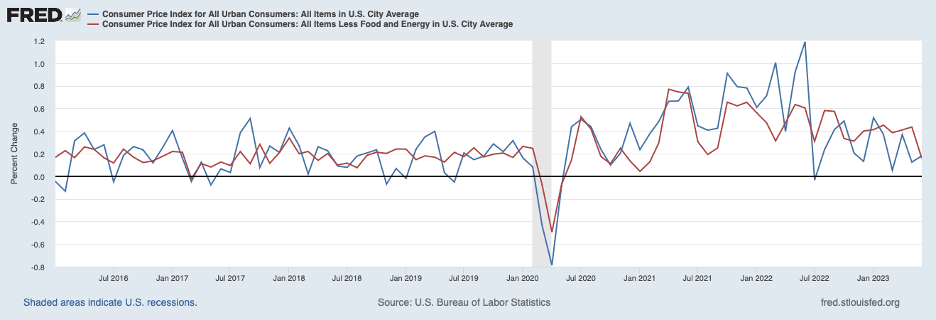

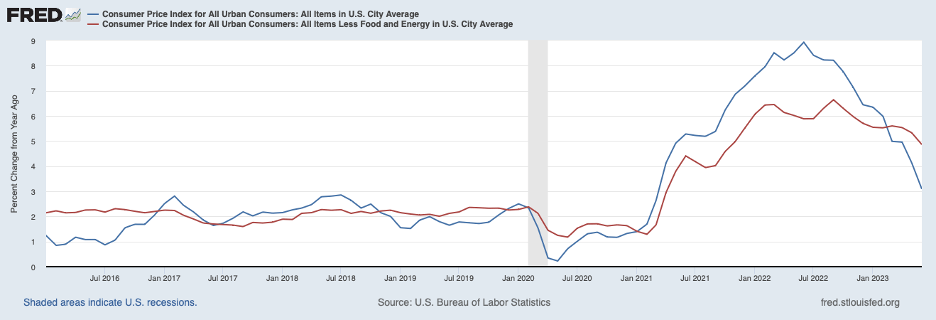

CPI inflation data for June came in below expectations, prompting a rally in financial markets and raising hope that inflation can be tamed without undergoing a recession—a so-called soft landing. The chart below shows that both headline (the blue line) and core CPI prices (the red line) posted 0.2 percent increases in June. For core prices, the June increase was the smallest since February 2021, and, if this pace were to continue in subsequent months, the Fed would be close to its 2 percent target for inflation.

The small increases in headline and core prices in June brought the twelve-month increase in core prices down to 4.9 percent, the smallest twelve-month increase since October 2021, and the twelve-month increase in headline prices down to 3.1 percent, the smallest increase since March 2021.

Before popping the champagne corks, one should consider how volatile are monthly CPI data. The first chart above amply shows that monthly percent changes in both CPI measures fluctuate a good bit, and the June CPI data may be providing more of a head fake than a signal that inflation is on a distinct downward path to the 2 percent target.

Indeed, the recent behavior of commodities prices in the CPI may be suggesting that the inflation process has more momentum than is widely believed. The table below shows the annualized three-month percent change in commodities prices excluding volatile food and energy prices (three-month changes have much less noise than month-to-month changes and better reflect trend).

Rate of Change of Commodities Prices Less Food and Energy

| Period | Annualized Percent Change |

| 2022 Q1 | 3.3 |

| Q2 | 5.0 |

| Q3 | 2.5 |

| Q4 | -2.1 |

| 2023 Q1 | 0.1 |

| Q2 | 4.3 |

This category of prices was little changed, on balance, over the two decades before the pandemic. However, during the pandemic supplies were constrained by supply-chain disruptions, and demand was boosted by federal COVID-related outlays and by consumers shifting their spending from services that involved social contact to commodities. As supply-chain pressures eased over the second half of 2022 and early 2023, commodities prices decelerated and even fell over the final three months of 2022. However, commodities prices resumed increasing over the second quarter of this year to a pace that exceeds what would be expected if inflation more broadly were headed downward to the Fed’s 2 percent target.

Does Disinflation Require a Recession (Economic Slack)?

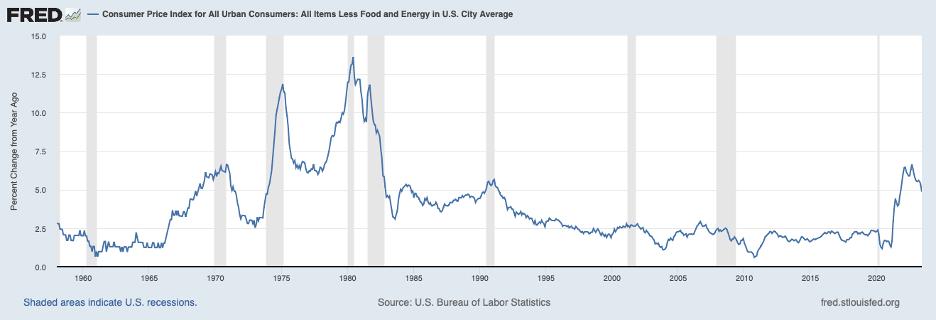

Moreover, historical experience clearly shows that periods of sustained disinflation occur during and just after recessions. The chart below shows twelve-month percent changes in core CPI prices—the same series shown in the first two charts but for a much longer period. The gray shaded areas represent recessions. For each recession, core CPI inflation fell appreciably. (For the 2007-2008 recession, inflation dropped to nearly zero but the drop fell short of predictions of economic models, and the drop in inflation in the 2020 recession was promptly followed by the current inflation brought on by extraordinary monetary and fiscal stimulus boosting demand coupled with supply-chain disruptions curbing supply). While economic principles tell us that high inflation can be brought down without a recession, historical experience tells us otherwise.

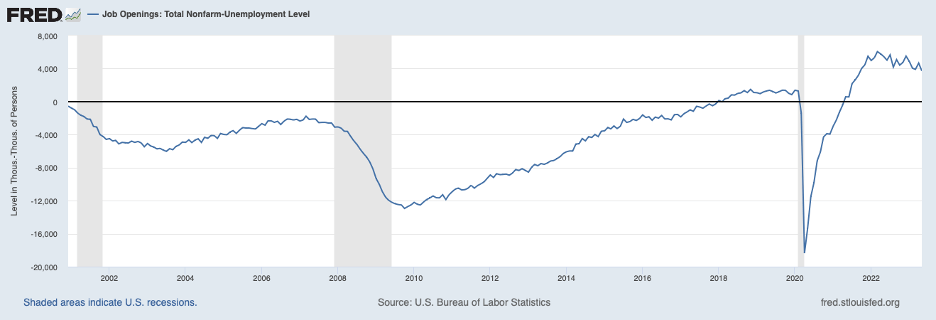

Judging from the labor market, the economy is not close to recession. The next chart shows the excess of job openings over the number of persons unemployed. This gap has narrowed slightly over recent months but remains well more than what has characterized periods preceding recessions. Moreover, recent news on retail sales and housing activity gives no hint that aggregate demand is about to collapse in the period ahead to the point that sufficient slack in the labor and product markets would develop to propel sustained consumer price deceleration.

Excess demand in the labor market continues to show through in wage growth. The next exhibit shows the Atlanta Fed’s wage tracker plotting the median twelve-month increase in hourly wages. This measure has moderated a bit over recent months but remains well above the pace that characterized the pre-pandemic period—a time of low inflation. Indeed, this measure of wages would need to decelerate around 2 percentage points to return wage-cost pressures to where they had been before the outbreak of inflation.

Headwinds

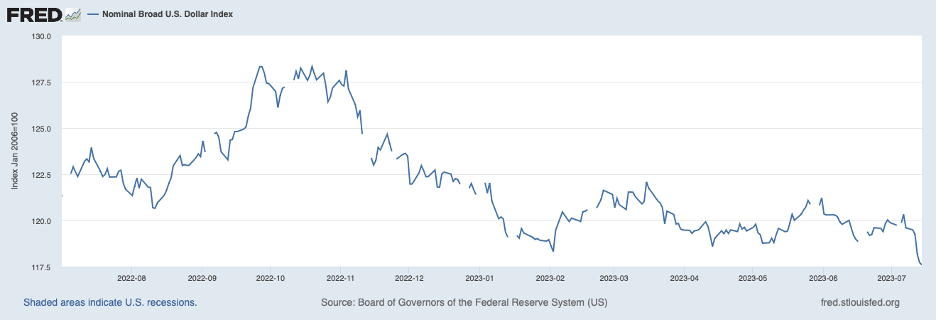

Some have voiced concern about headwinds facing the U.S. economy that might be pushing the U.S. economy into recession soon, implying that the Fed need not tighten any more. Among the frequently mentioned headwinds has been the slowdown in the Chinese economy which could put a big crimp in the demand for U.S. exports. However, the weakening of the demand for exports caused by the Chinese slowdown will not be sufficient to throw the U.S. economy into recession, and the sliding value of the U.S. dollar, shown next, will provide some offset through cheaper U.S. exports to foreign buyers.

Another headwind raising concern of late is the impact of the recent Supreme Court decision overturning the executive branch’s order on student loan debt relief. The worry is that the resumption of debt payments on student loans will have a large depressing impact on household spending. Whether the resumption of payments on these student loans has much depressing effect on spending depends on the extent to which the highly uncertain legal status of the debt relief order had spawned caution and spending restraint on the part of student loan debtors. In such circumstances, spending will not be much affected by the ruling.

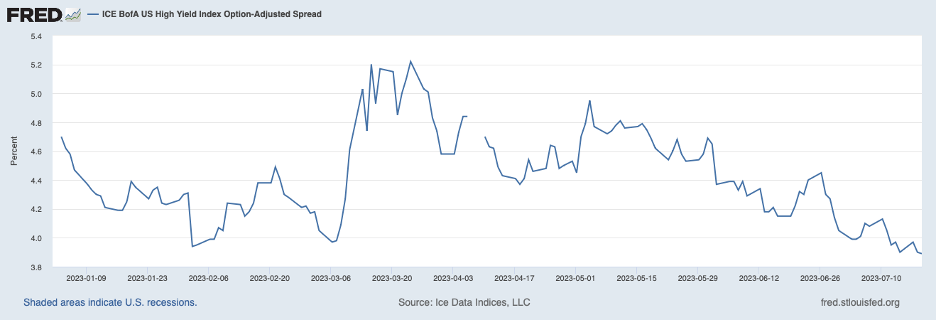

A headwind that has influenced the thinking of Fed policymakers over recent months is the impact on the provision of credit of the shock caused by the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and a couple of other banks in early March. The concern is that bankers might be responding to the shock by cutting back on lending. There is not much in the way of real-time data on bank lending conditions, but we can make inferences from credit spreads on market-traded instruments and reports on bank funding markets. The following chart shows the interest rate spread on below-investment-grade bonds and this spread is an indicator of the appetite of market participants for risk. The chart shows that the risk premium surged in early March when SVB failed but has since fully retraced that increase. In addition, reports indicate that bank funding markets have been stable in recent months. In these circumstances, it would seem that the SVB shock is not posing much of a headwind through lending conditions in the bank credit market.

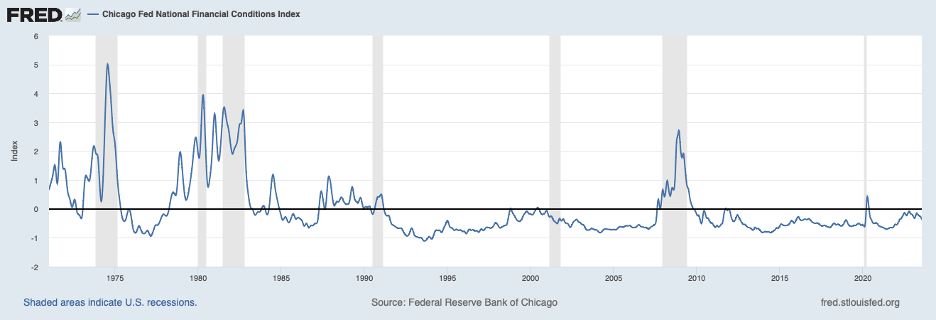

Similarly, it is hard to find evidence of headwinds more broadly in financial markets as shown by the Chicago Fed National Financial Conditions Index—chart below. The chart illustrates that financial conditions are not restrictive by historical standards and are only a little less accommodative than just before the March SVB shock.

Another potential headwind comes from the impact of fiscal policy on growth in output, especially as federal outlays coming from the massive spending bills of recent years taper down. Shown below is the impact of fiscal policy on growth estimated by the Hutchins Center at the Brookings Institution. The chart shows that the drag coming from fiscal policy has been diminishing and is projected to continue to do so. Thus, the headwind on growth coming from fiscal policy is behind us.

Implications for Monetary Policy

Based on the evidence reviewed, it would be premature to conclude that the back of inflation has been broken. The slack that has accompanied previous cases of stubborn inflation has yet to emerge, and the prospects for headwinds that would push the economy into recession and bring down inflation seem remote at the current time. While it is true that the recent performance of the economy and inflation has some unique features, it is wishful thinking to conclude that this uniqueness means that disinflation will come painlessly. Thus, the Fed should proceed to raise its target for the federal funds rate at coming meetings and convey that further rate boosts may be needed unless the consumer price data over coming months more convincingly show that inflation is broadly on a sustained downward path—an unprecedented soft landing has finally been achieved.