A widespread view has developed that the Fed has slayed the inflation beast and that declines in interest rates are just around the corner. Participants in the federal funds futures market have priced in declines in the target for the federal funds rate starting next spring and continuing through the rest of the year. They see the federal funds rate as being lowered 1-1/2 percentage points from its current range of 5.25 to 5.5 percent over the next year. In contrast, in its most recent set of projections, the Fed envisions a smaller decline over the next year — about ¾ percentage points.

What Does the Data Say?

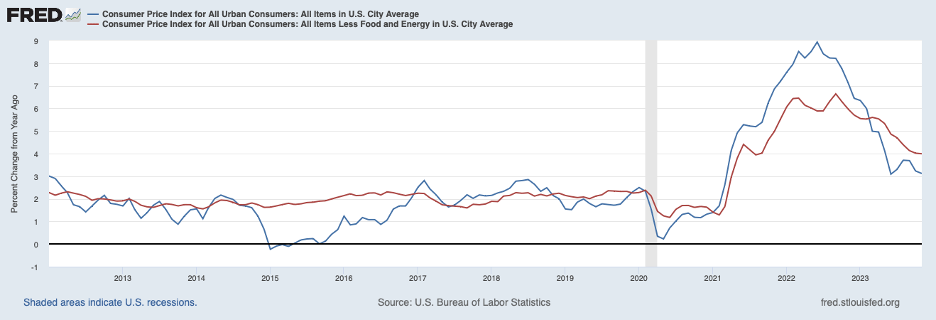

However, a careful reading of the consumer price index report (CPI) for November should give the Fed and market participants some pause. The twelve-month headline CPI increase was 3.1 percent — the blue line in the chart below — down 4 percentage points from a year earlier. The twelve-month change in the core CPI, which excludes food and energy prices — shown by the red line below — stayed at 4 percent. However, the annualized percent change in core inflation over the three months ending in November fell to 3.3 percent.

To be noted is that these seemingly benign price changes are masking developments that point to underlying inflation being more stubborn and more difficult to curb.

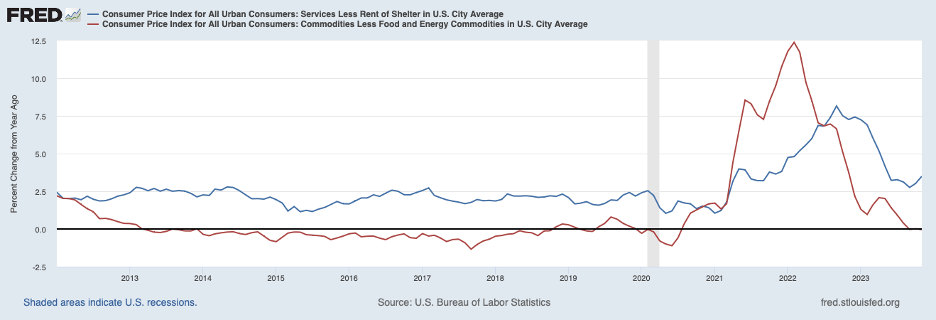

The following chart shows increases in CPI prices of services excluding shelter (the blue line) and commodities excluding food and energy (the red line). Service price inflation was 3.5 percent over the twelve months ending in November, a full percentage faster than before the pandemic, and picked up to 4.3 percent at an annual rate over the three months ending in November.

The red line shows that commodity prices have been flat over the twelve-month period ending in November. Declines in commodity prices over recent months offset increases earlier in the period. Indeed, commodity prices fell at more than a 3 percent annual rate over the three months ending in November. The recent decline exceeds small decreases in commodity prices before the pandemic and likely reflects a further unwinding of supply chain disruptions that added to price pressures in 2021 and 2022.

Putting the Pieces Together

Commodity prices cannot be expected to continue to fall at the rate they have been in recent months and, before long, will not be dragging down CPI inflation as they have recently. Meanwhile, service prices can be expected to continue to rise more rapidly than is consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent target for inflation.

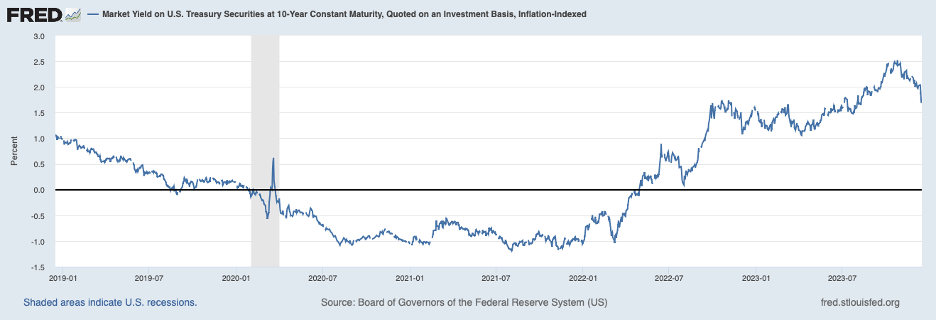

These findings suggest that Fed policy needs to remain restrictive to apply sufficient restraint on inflation to achieve the Fed’s 2% inflation target. The chart below shows the real interest rate taken from the market for ten-year Treasury Inflation-Indexed securities. This real rate — at around 1.7 percent — is much more restrictive than it was two years ago before the Fed began to tighten monetary policy. But the real rate is less than a percentage point above the neutral real rate — the interest rate that is neither expansionary nor contractionary. Moreover, the bulk of the increase in the real interest rate took place more than a year ago and is probably not holding down growth in output much at this point.

Going Forward

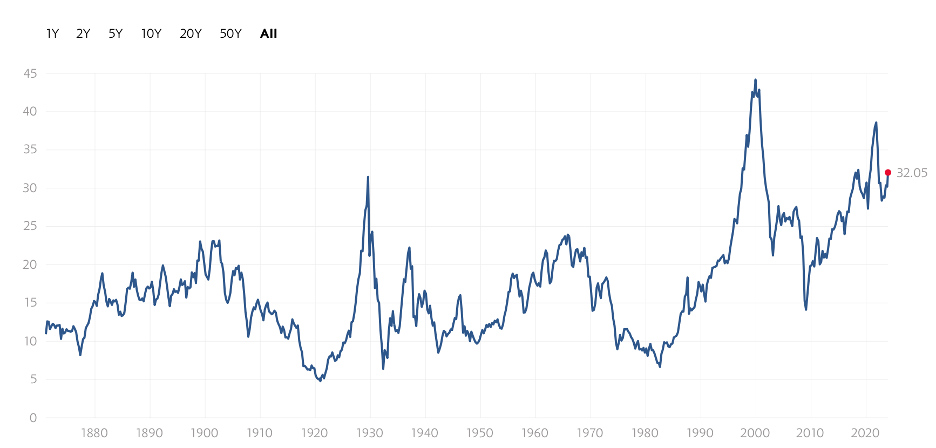

Indeed, recent labor market data — the labor market report for November and weekly initial claims for unemployment insurance through early December — along with retail sales for November suggest that underlying growth in output remains solid but at an unsustainable rate. No doubt the lofty stock market, shown below, with share prices approaching their record high, is helping to fuel this growth.

The following chart shows that share prices are also high in relation to (cyclically adjusted) earnings. With real interest rates somewhat high, the elevated cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio suggests a vulnerability going forward. A correction in the stock market cannot be ruled out.

As the Fed assesses policy risks going forward, policymakers should be mindful that there still is a way to go before it has achieved its inflation goal and that the inflation process has a persistence that is not fully understood. The implication of recent data is that the Fed needs to hold a restrictive posture for a while longer. Also, the costs caused of erring by easing too early will ultimately exceed the costs of erring by easing too late. The Fed’s job would be made easier if market participants turned to the other hand and repriced longer-term interest rates higher and share prices lower.

Header image credit: Randy Fath/Unsplash