The CPI for May prompted euphoria in financial markets and restored expectations of rate cuts by the Fed in the months ahead — the first in September and another by year-end. The S&P 500 stock index rose nearly 1 percent on the day and tacked on another ¼ percent gain the following day.

May CPI Data

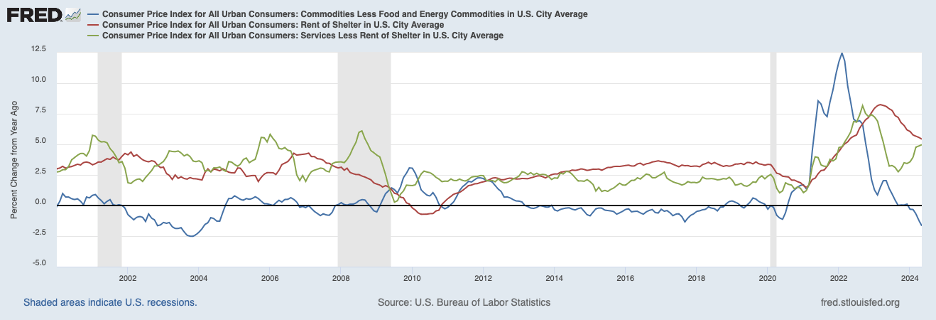

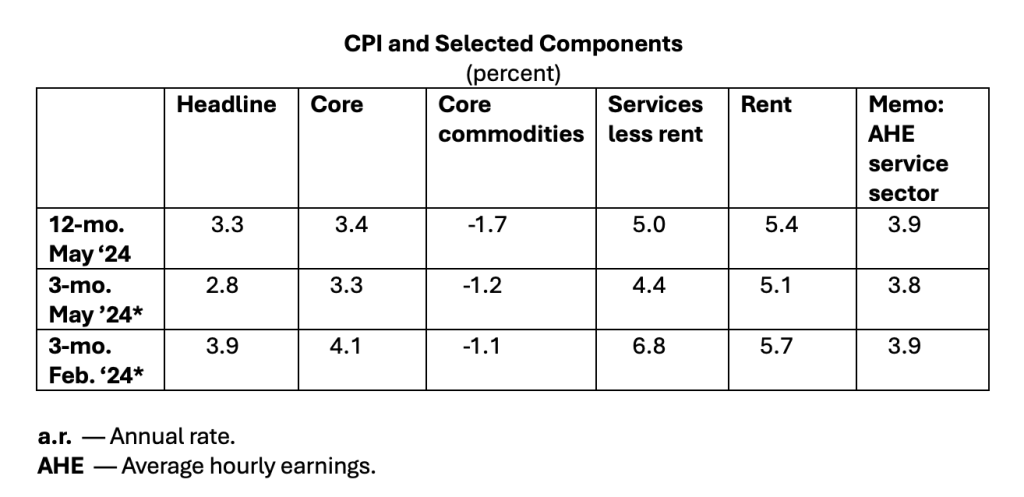

The headline CPI for May was unchanged, and the core CPI (which excludes volatile food and energy prices) registered its smallest increase — 0.2 percent — in ten months. Both readings were below market expectations. Incorporating the May CPI data, the twelve-month change in the headline CPI ticked down to 3.3 percent, shown by the blue line in the chart below, and the twelve-month change in the core CPI, the red line, edged down to 3.4 percent, the smallest twelve-month increase since April 2021.

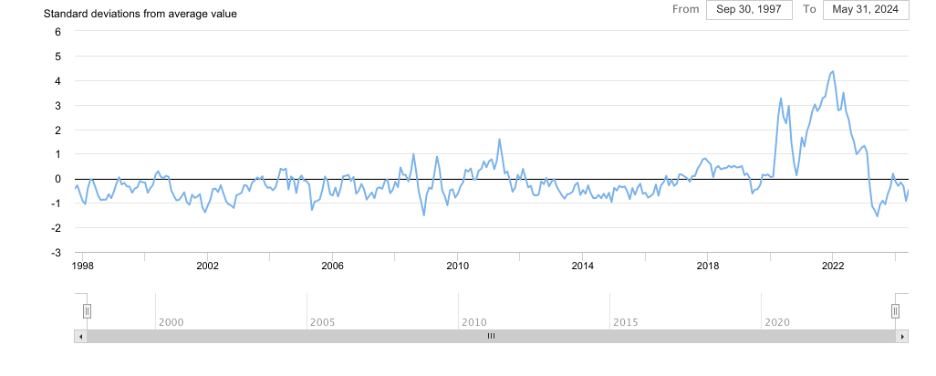

Ordinarily, the core measure of inflation is a reliable indicator of underlying inflation. However, in the past couple of years, the core measure has been buffeted by supply-chain disruptions and their effects on commodity prices included in the core CPI. Initially, supplies were constricted by greater supply chain pressures, shown by the increase in the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index in the chart below.

Global Supply Chain Pressure Index

Consequently, core inflation surged as illustrated by the blue line below. Once supply chain bottlenecks were fixed, supply chain pressures began to unwind and prices of commodities retraced a portion of their previous increase. This retracing contributed to a considerable slowing in core inflation. More recently, supply chain pressures appear to be normalizing. With the normalization, the contribution of commodity price declines to disinflation is drawing to an end.

Consumer Shifts

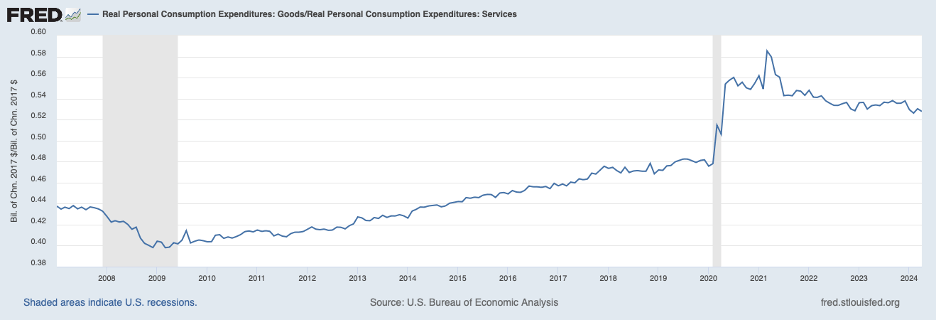

A consumer shift from services to commodities has added to the swings in commodity prices. At the onset of COVID, people started to shift away from services, such as restaurants and air travel, and toward tangible commodities. This can be seen in the following chart, which shows the ratio of commodities purchases to services purchases. This ratio spiked in 2020 and has unwound only a portion of that spike since then.

The swing toward commodities added to the surge in prices of commodities, shown above. Once the ratio of commodities to services stabilized, its impact on commodity prices faded. It’s worth noting that shifts in preferences for commodities versus services do not have much impact on overall inflation, as the upward pressure on the prices of commodities is at least partially offset by downward pressure on the prices of services.

Rent of Shelter

Another factor that has tended to distort the core CPI as a measure of underlying inflation is the rent of shelter. As shown by the red line in the chart above, this component of the core CPI surged from less than a 2 percent rate of increase in early 2021 to a peak of 8 percent in early 2023 and has fallen to a 5.5 percent rate most recently. Other information on newly negotiated rents suggests that rent increases have slowed more than what is being captured in the core CPI and thus may be working toward overstating the core measure of inflation.

In light of the distortions coming from prices of commodities and rent of shelter, a more reliable gauge of underlying inflation may be prices of services excluding rent, shown by the green line in the chart above. On a twelve-month change basis, this component rose sharply over 2021 and much of 2022, then retraced the bulk of that acceleration until the fall of 2023. Since then, twelve-month increases in service prices have been heading back upward. The twelve-month increase over the period ending in May 2024 was 5 percent, roughly 2-1/2 percentage points faster than the period before the pandemic.

The table below shows that prices of services less rent rose at a less rapid 4.4 percent annual rate over the three-month period ending in May which could be a signaling an easing in underlying inflation. However, these service prices still have a sizable amount of deceleration to go before returning to a rate consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent target. (It’s also worth noting that the Fed specifies its inflation target in terms of the PCE — Personal Consumption Expenditures— index and not the CPI. The PCE index tends to increase slower than the CPI, on the order of ½ percentage points per year.)

Labor Cost Pressures

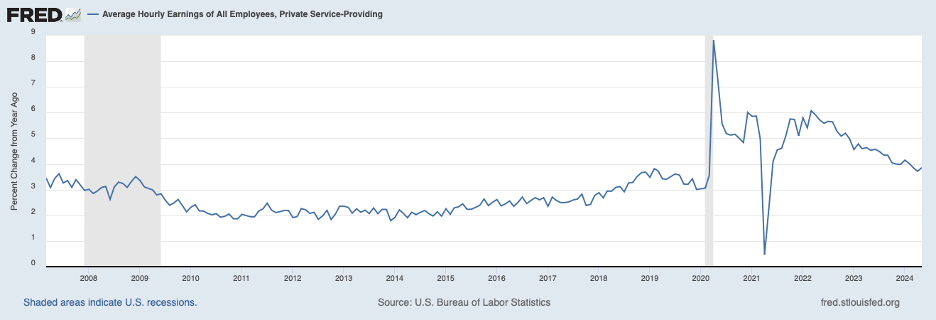

Labor cost pressures are another consideration in assessing underlying inflation, especially in the service sector. The following chart shows twelve-month increases in average hourly earnings in the private service sector. The chart and the table above indicate that this gauge of labor costs is leveling out at just under 4 percent at an annual rate, roughly one percentage above the rate over the decade before COVID.

In assessing the underlying inflation rate, a couple of additional factors likely have been temporarily holding down inflation measures. One is the dollar appreciation over the past year, restraining increases in import (and import-competing) prices. The other is the surge in immigration in recent years, which is putting downward pressure on wages and labor costs. Once these forces are reversed, their impact on holding down inflation will disappear.

Is Inflation on a Downward Trajectory?

Pulling together wage and CPI data, it seems premature to conclude that underlying inflation is on a downward trajectory toward the Fed’s 2 percent target. Instead, it may well be that underlying inflation is settling into a rate that is one percentage point or more above the Fed’s target Consistent with this assessment, it seems that consumers have come to expect higher inflation than in the pre-pandemic period, as shown by the Michigan Survey Research Center of expectations of inflation over the coming year. This measure of inflation expectations continues to run well above expectations in the pre-COVID period and has turned up recently. (A somewhat similar story is told by longer-term expectations of inflation by consumers in the Michigan survey.)

The inflation problem has also caught the attention of businesses. In the most recent survey of the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), inflation was identified as the most serious problem confronting small businesses. As a result, the behavior of consumers and businesses is being affected in ways that are influencing the dynamics of the inflation process and making inflation more intractable.

Interest Rates

If the prospects for further disinflation are less than favorable, then real interest rates must be higher to apply sufficient restraint to the economy. The next chart shows the real interest rate on the ten-year inflation-indexed note that serves as a benchmark for the interest rates that influence business and consumer spending decisions and, thereby, output and employment growth. This real rate has been edging down since the May CPI report and is not particularly high by the standards of the past couple of decades.

At issue is whether slack in labor and product markets will be needed to bring underlying inflation down to 2 percent — a recession. Historical experience indicates that slack in these markets will be needed to get inflation on a sustainable path downward, especially once it has become entrenched.

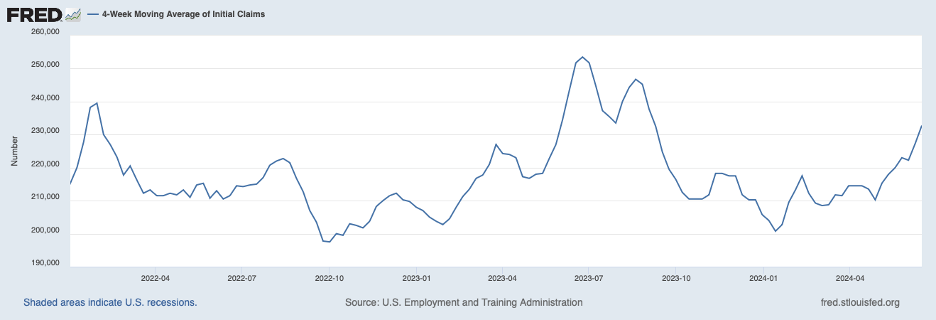

The labor market has been cooling a bit judging from initial claims for unemployment insurance, shown as a four-week average in the chart below.

Claims have been edging up over recent weeks, but they are not very high which points to a still-strong jobs market. (The increase in the unemployment rate in May to 4.0 percent resulted from a decline in employment of more than 400 thousand, according to the household survey for that month. This contrasts with the 270 thousand increase in employment in the more reliable establishment survey, an increase that exceeds the required employment gain to keep the unemployment rate unchanged.)

Furthermore, output growth appears to still have momentum. A model used by the Atlanta Fed estimates output growth to be 3 percent in the second quarter, a full percentage point faster than the sustainable rate of output growth. In these circumstances, movements toward gaps in product and labor markets will not be forthcoming unless interest rates increase.

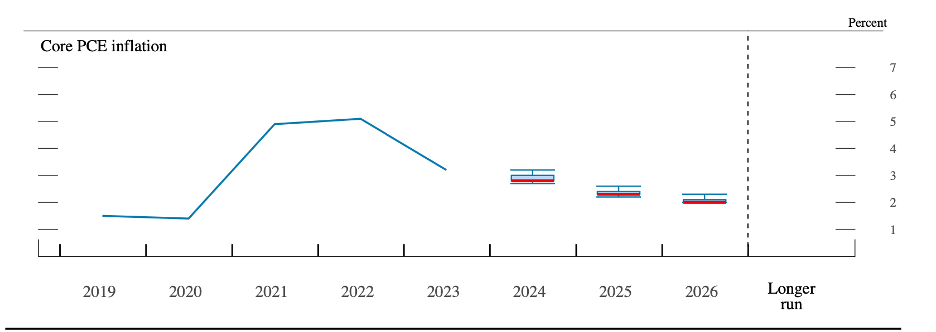

However, the view that interest rates need to be moving higher to bring down inflation is not the view of Fed policymakers. Below is Fed policymakers’ most recent forecast of core PCE inflation. The solid blue line shows the actual rate through 2023 and the red bars show the median forecast for 2024 and the following two years. As can be seen, the median forecast drifts down to the 2 percent target in 2026.

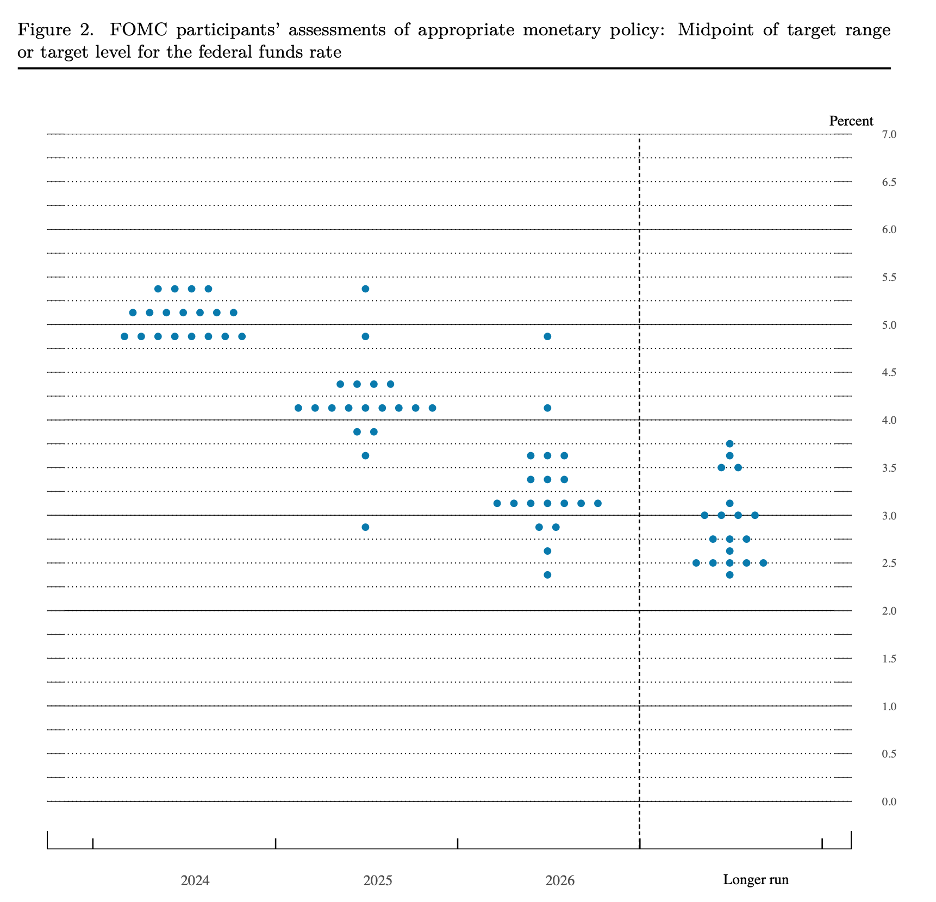

Moreover, this reaching of the inflation target is achieved without any increases in the target for the federal funds rate. Indeed, the following chart (“dot plot”) shows that the median Fed forecaster envisioned that the target for the federal funds rate will drop 25 basis points this year, 100 basis points in 2025, and another 100 basis points in 2026.

Can the Fed Achieve a Soft Landing?

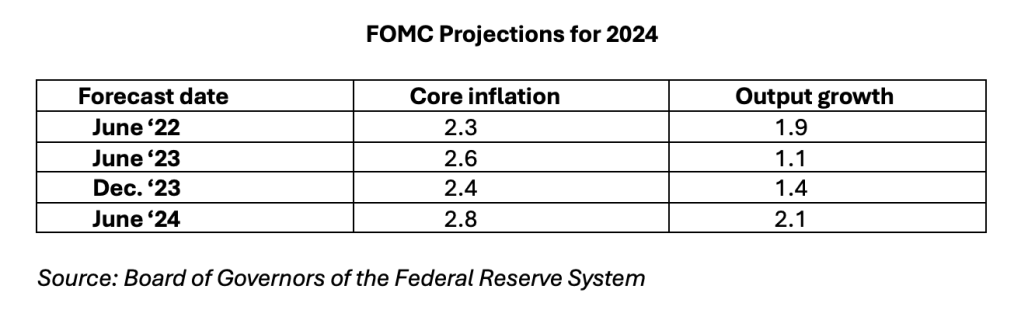

Fed policymakers may be correct, and a soft landing can be achieved without any further increases in the target for the federal funds rate. However, the Fed has regularly underpredicted inflation in recent years and needs to revise its projection upward for core PCE inflation. This is illustrated in the table below, which contains projections of core inflation and output growth for 2024 at different times in the past. Indeed, the median forecast for core PCE inflation has been revised upward by 0.4 percentage points since last December from 2.4 to 2.8 percent. To achieve this forecast, monthly increases in the core PCE index will need to slow to just under 0.2 percent over the remainder of the year from 0.27 percent for the period through May.

Note: The Fed typically projects PCE inflation and not the more common CPI inflation. PCE inflation tends to be a little lower than CPI inflation.

In light of the considerations above, some skepticism about returning to 2 percent inflation without higher interest rates seems appropriate. Accordingly, financial markets and the Fed must prepare for further policy tightening. Unless events unfold along the lines of the Fed’s most recent forecast, the sooner interest rates increase sufficiently to place inflation on a distinct downward path, the sooner we can again experience the benefits of stable prices.

Featured Image: Albin Berlin/Pexels