Few developments have received the attention that artificial intelligence (AI) has received in recent years. Much of that attention has been focused on concerns about job losses, invasions of privacy, and the dangers of self-driving cars, trucks, and buses.

Although often forgotten, AI has been around for some time. Computers have been performing highly complex calculations much more accurately and faster than humans. High-tech toll collection systems have been replacing human-staffed toll booths, GPS systems have been guiding our travels instead of maps, spreadsheets have simplified a wide variety of tasks, and robots have taken positions on assembly lines for cars and trucks and have even become restaurant servers. Consequently, many jobs have been displaced. But it is worth noting that the job market has been strong in recent years as job vacancies have been exceeding unemployed workers.

What Are the Implications of Automation?

The primary motivation for this automation is to utilize technology to replace tasks performed by individuals and thereby trim labor costs. Those investing in such automation believe that the labor cost savings will justify the cost of the investments. Can we expect forthcoming automation to be on a grander scale and to cause more joblessness than in the past? What are the implications for how rapidly the economy can grow, for inflationary pressures, and for Fed policy?

Automation has the effect of boosting labor productivity. In other words, more output can be produced with the same number of workers — output per hour of employment increases. More output means more income for at least some — especially the entrepreneurs, business owners, and workers implementing and utilizing AI. This process can also lead to a greater variety and a better quality of products in the marketplace and frequently lower prices for buyers.

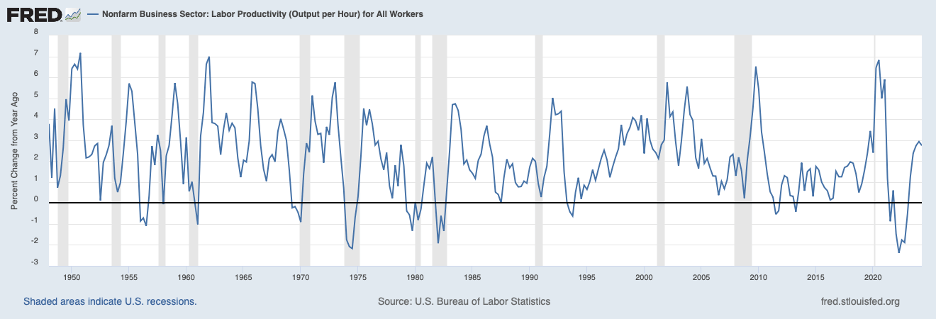

Labor Productivity

Labor productivity has been growing over the United States’ history and has been the primary reason for growth in real wages and the American standard of living. The chart below shows growth in labor productivity in the nonfarm business sector over four-quarter periods for the past three-quarters of a century. Growth in productivity fluctuates greatly, but there are a couple of features of such growth that are worth noting.

First, labor productivity typically declines in recessions — the grey-shaded bars — but rebounds smartly early in economic expansions. Second, productivity growth during economic expansions — periods between the shaded bars — has varied significantly. Third, the most recent period of rapid, sustained productivity growth was from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s. During this period, productivity grew at a 3.1 percent annual rate. This growth is to be compared with 2.1 percent annual growth in productivity over the four-decade period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1990s and only 1.0 percent annual growth over the nine years before the onset of the COVID pandemic in early 2020. (Worth noting is that 1 percent annual growth in output per worker leads to a doubling in the standard of living over a little more than three generations.)

Brisk productivity growth in the decade starting in the mid-1990s has been attributed to developments in information technology (IT), especially the Internet. Moreover, the second half of the 1990s was also characterized by a stock market frenzy linked to IT developments, which led to the so-called “dot com bubble.”

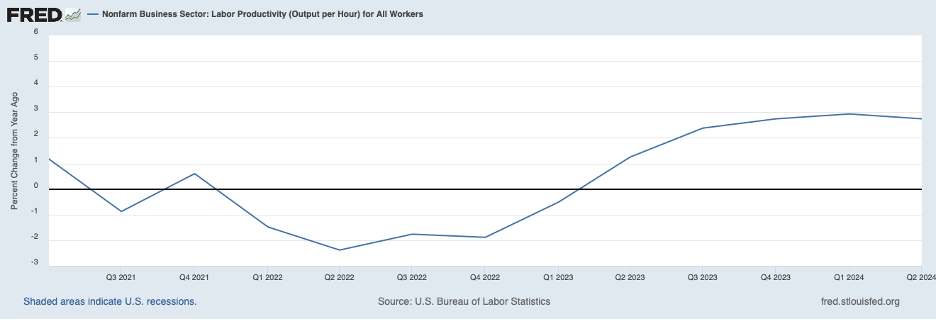

The most recent period is shown in the following chart, presenting productivity growth from the start of 2021 through the second quarter of 2024 (most recent data). Productivity declined slightly over 2021 and 2022 (productivity growth was negative) but turned up in early 2023. Productivity has been increasing at a robust 3 percent annual rate over recent quarters. Could we be on the cusp of another surge in productivity similar to that around the turn of the century, this time coming from AI?

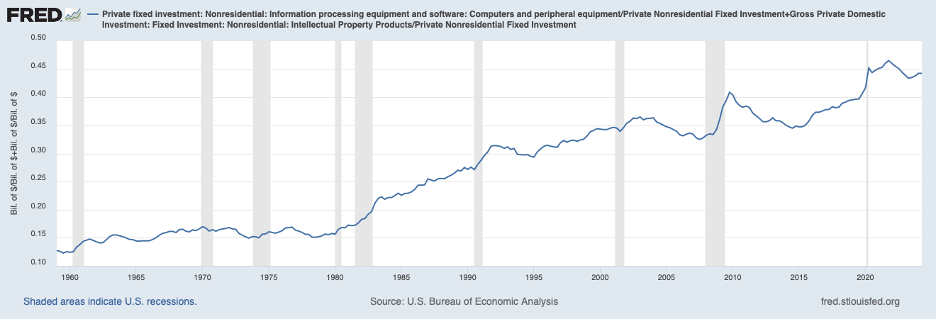

Playing a key role in whether we are on the verge of another era of rapid productivity growth, this time AI-related, will be business investment in research and development (R&D) and IT equipment and software. R&D investment involves exploring ways AI can be developed and utilized for business purposes, and IT equipment and software investment involves its application. The chart below shows that investment in R&D (intellectual property products), IT equipment, and software has soared since early this decade.

Moreover, the next chart shows that the share of total business investment going to R&D and IT has climbed to an all-time high this decade.

Is This Evidence Confirming That We Should Expect More Rapid Growth in Productivity and Output in the Period Ahead?

While it seems reasonable to expect a noticeable pickup in growth in productivity from the pace we experienced over the previous decade, the timing of this pickup is uncertain. How rapid innovation gets translated into growth in productivity and output is not fully understood and can take some time. For example, the charts above show that the decade of the 1980s into the early 1990s was a period of large investments in R&D and IT, but it took a catalyst around the mid-1990s — the Internet — to translate those investments into productivity and output yields.

One indicator that likely will foreshadow a period of rapid productivity gains will be corporate profits. Once business output picks up in relation to labor input (productivity picks up), the initial beneficiary will be corporate profits. Over time, competitive forces will cause businesses to spread these gains to workers in the form of faster wage growth.

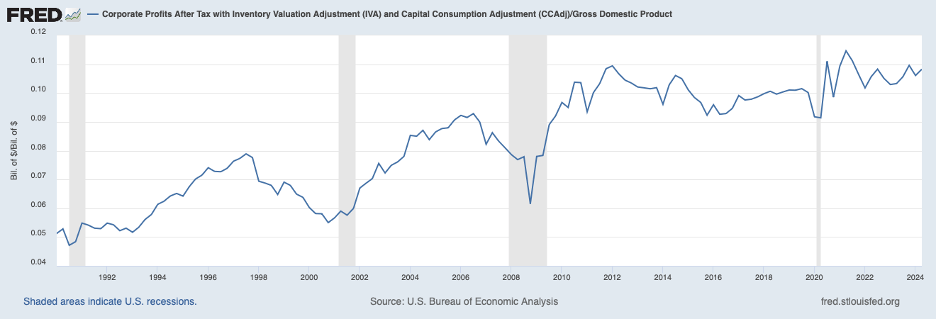

Shown next is the corporate profit share of GDP. It’s worth noting that several things impact corporate profits, including innovation and resulting productivity gains. Looking at the 1990s, profits climbed to very high levels around mid-decade and beyond before businesses were under competitive pressures to share these gains with workers. Fast forwarding to now, the chart shows that the profit share reached new highs in recent years and has been on a mild upswing over the past two years. The high and rising profit shares may signal that productivity is starting to get a boost from investments in AI.

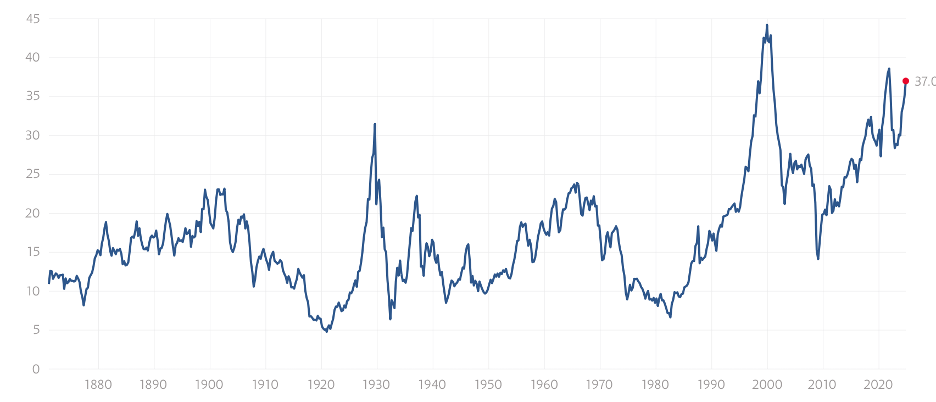

The equity market likely has gotten a lift recently from optimism about the outlook for corporate earnings coming from investments in AI. The next chart shows the Shiller cyclically adjusted price-earnings (P-E) ratio for the S&P 500. This ratio, at a share price of 37 times earnings, is well above the historical average of 17 and not much below the peak reached on the eve of the bursting of the dot.com bubble of the late 1990s. (To a degree, the current high P-E ratio reflects long-term interest rates on the low end of historical averages.)

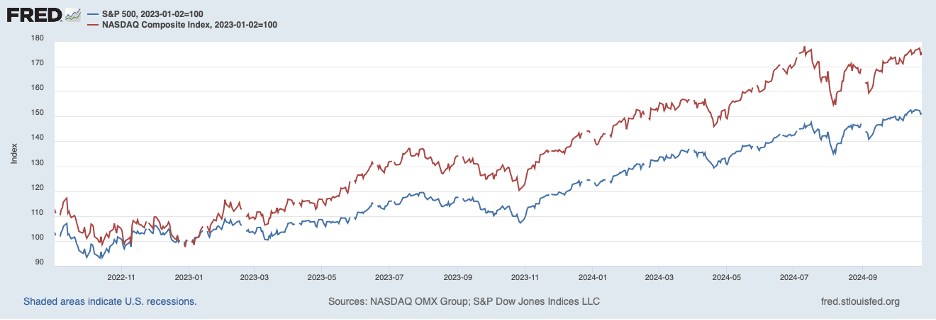

Moreover, an indicator of market sentiment toward tech stocks can be seen in the next chart, showing the behavior of the S&P 500 stock price index (the blue line) and the tech-laden Nasdaq over the past two years. The chart shows that the Nasdaq has considerably outperformed the S&P (which itself has a significant tech component) over this period.

What Does It Mean for the Economy and Monetary Policy if We Enter an Era of Greater Productivity Growth From AI?

In these circumstances, growth in potential output will be picking up. The growth in potential output, as a first approximation, is the rate of growth of productivity plus the rate of growth of the labor force. In the future, we can expect the growth rate of the labor force to be roughly ½ percent per year if immigration, which has been swollen in recent years, returns to historical norms. Should underlying productivity growth increase one percentage point because of AI, from 1-1/4 percent per year (roughly the rate in the decade before COVID) to 2-1/4 percent per year going forward, growth in potential output would increase from 1-3/4 percent to 2-3/4 percent. This would make an appreciable difference in improvement in the standard of living in America and in government finances (faster growth in output in the latter part of the 1990s resulted in a huge improvement in tax revenues).

An increase in growth in potential output can be thought of as an increase in the growth of aggregate supply. By itself, this increase in the growth of aggregate supply would put downward pressure on the inflation rate. However, the extra output being produced also adds to the income of members of the economy, which boosts aggregate demand. As noted above, much of this additional income initially takes the form of profits and later takes the form of wages. The implications for aggregate demand depend on whether spending out of profits (which gets built into share prices) differs from spending out of labor income. Some researchers have found that spending out-of-labor earnings tends to be greater than out-of-profits. If so, an upturn in productivity growth could result in aggregate supply growing faster than aggregate demand until the gains in productivity get translated more fully into wage growth.

All of this poses challenges to the Fed as it seeks to attain its statutory goals of maximum employment and stable prices. First, the Fed needs to discern whether AI is boosting growth in productivity and output. As noted above, there are early signs of an upturn in productivity revealed by faster growth in measured productivity and a higher profit share. Second, the Fed will need to decide how the resulting faster growth in potential output affects the aggregate supply-aggregate demand balance. If it is leading to faster growth in supply than demand, then the situation may call for a reduction in its target for the policy interest rate to stimulate more demand and avoid slack from emerging. If, instead, both growth in aggregate supply and demand pick up by similar amounts, the situation would not call for any changes in the policy rate. Stay tuned.

We’ve Been Through This Before

In any event, as innovation in AI gains traction, there will be job losses from AI as there have been job losses stemming from innovation in the past. Also, as in the past, there will be job gains for those playing a role in these innovations. Furthermore, there will be new jobs for those producing the goods and services being purchased with the extra income created by the innovation process as the size of the economic pie expands from AI. We’ve been through this before.

Header Image: Taylor Vick/Unsplash