Market participants expect the Fed to lower its target for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points on December 18, aided by some signals from Fed policymakers that they are inclined toward such a move. Do recent data support such an action?

The recent behavior of consumer prices and developments in the labor market play a key role in the answer to this question. The November CPI release revealed that both headline and core CPI rose 0.3 percent last month (which translates to 3.7 percent at an annual rate). As a result, the twelve-month increase in the headline CPI was 2.7 percent, up from 2.6 over the twelve-month period ending in October (the blue line in the chart below). The twelve-month increase in the core CPI (which excludes volatile food and energy prices) stayed at 3.3 percent in November (the red line).

Converting the CPI news to the Fed’s preferred measure of consumer prices, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index, suggests that that headline PCE will be up 2.6 percent from the fourth quarter of 2023 and core PCE will be up 3.0 percent — both notably higher than the Fed’s 2 percent target.

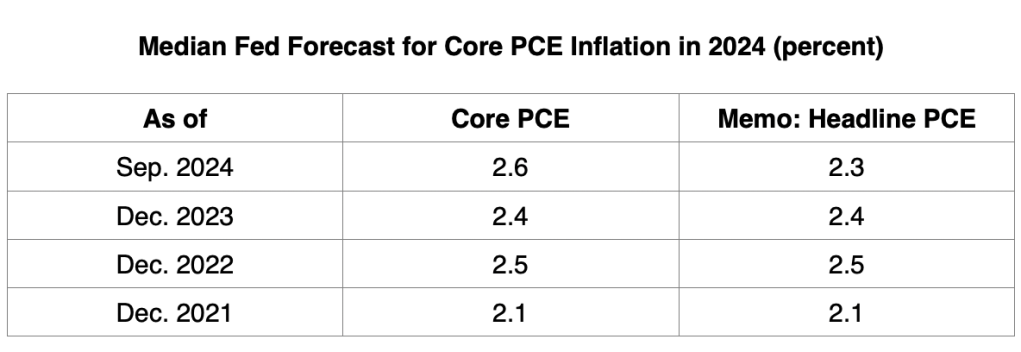

If the core PCE ends the year up by around 3 percent, the Fed will have again underpredicted core inflation. The table below shows the median forecast of core PCE inflation in 2024 by Fed policymakers as of various dates in the past. In December 2021, the Fed projected that core PCE inflation would be 2.1 percent this year, marginally above the target. By September this year, that forecast had been raised to 2.6 percent. Based on the November CPI, that forecast will need to be raised further in December.

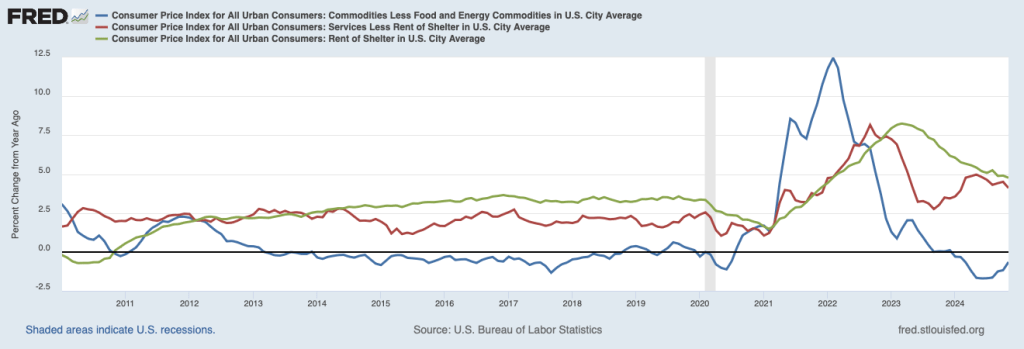

Analysts, including Fed policymakers, have pointed to special factors that have affected inflation over recent years: supply chain disruptions linked to the COVID pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which curtailed energy supplies, and a jump in the demand for shelter (reflecting, at least in part, the surge in immigration). These factors have led to cross currents in the principal components of consumer prices. Shown below are twelve-month changes in the core commodities component of the CPI (the blue line), the services less rent of shelter component (the red line), and the rent of shelter component (the green line).

The core commodities component soared in 2021 and 2022 owing to disruptions to global supply chains associated with the pandemic, but subsequently, those movements were unwound, and the twelve-month change in core commodity prices has turned up. Indeed, core commodity prices have increased at a 1.5 percent annual rate over the three months ending in November, a good bit above the small declines before the pandemic.

The twelve-month increase in service prices excluding shelter edged down in November, but at 4.1 percent, it was more than 1/2 percentage point higher than a year earlier. Moreover, the increase in service prices, excluding rent of shelter over the three months ending in November, was 4.4 percent, well above the pre-COVID period and raising doubts about whether this important component of consumer prices is slowing.

Turning to rent, increases in rent have been steadily declining for some time, continuing through the three months ending in November. Based on other information, a deceleration in rent has been expected for some time, but the process has taken longer than had been thought.

Summing up this discussion of CPI components, commodity prices have stopped declining and may have more upward momentum than before the pandemic. The deceleration in service prices, excluding rent of shelter, shows signs of stalling in recent months at a rate that is well above the pre-COVID period. Against this backdrop, progress toward the Fed’s 2 percent target for consumer price inflation could be impeded by further monetary easing.

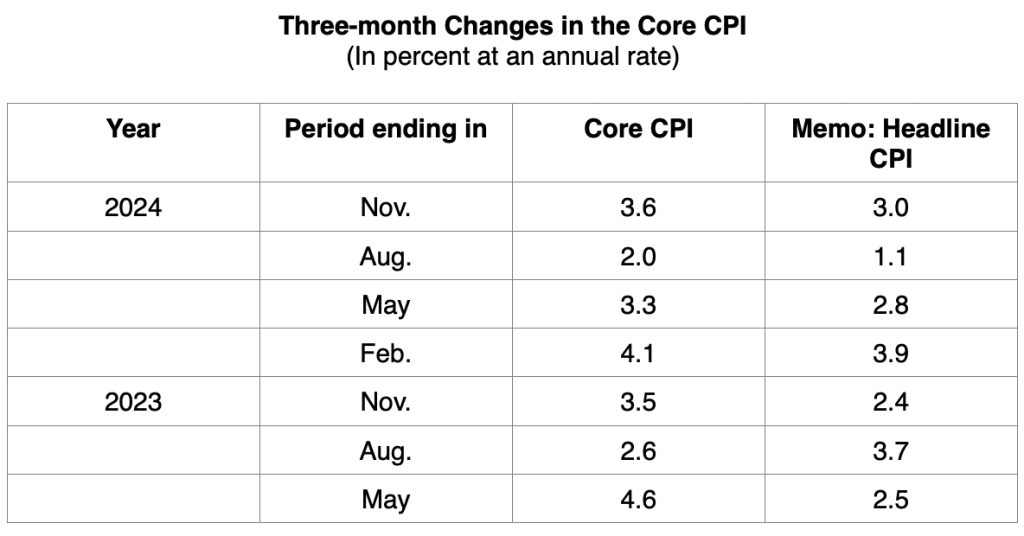

Some analysts have argued that methods used for seasonally adjusting consumer price data may distort recent inflation trends and may not reveal ongoing deceleration in consumer prices. The table below sheds some light on this matter. It shows annualized core CPI inflation for three-month periods ending in the month listed.

If there has been a slowing in underlying core inflation in 2024, it would be more evident in comparisons of the same three-month periods from 2023 to 2024 than in looking for patterns in individual months. Such a slowing in core inflation is revealed in the three-month periods ending in May and August. However, core inflation ticked up in the three-month period ending in November, raising doubts about whether progress continues in reaching the Fed’s inflation target.

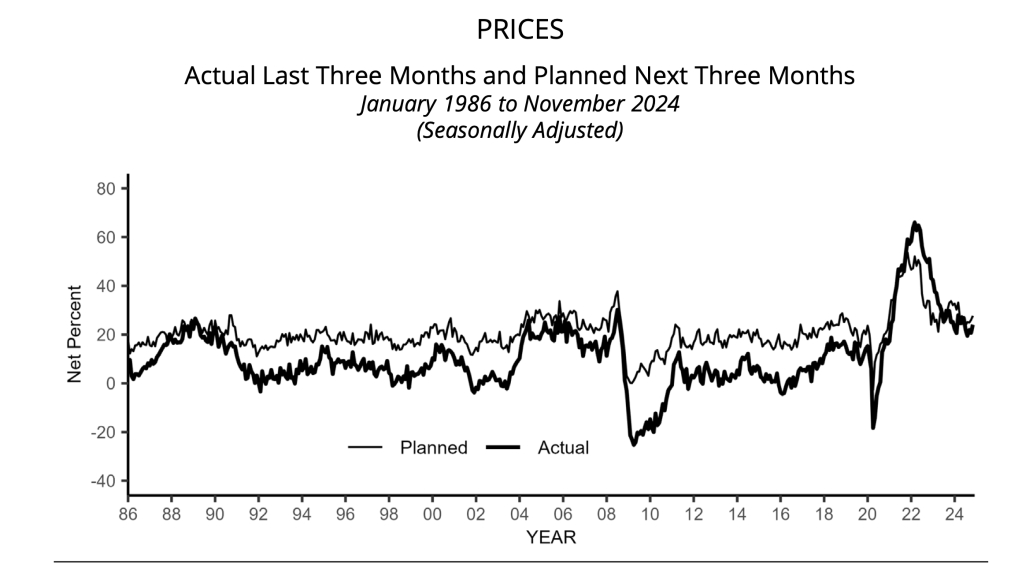

The most recent survey of small businesses by the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB) confirms that inflation will likely remain stubborn in the months ahead. The thin line in the chart below shows that the proportion of respondents planning to raise prices over the next three months remains high and actually has edged higher over recent months. (The thick line shows the proportion of respondents who had raised prices over the past three months.)

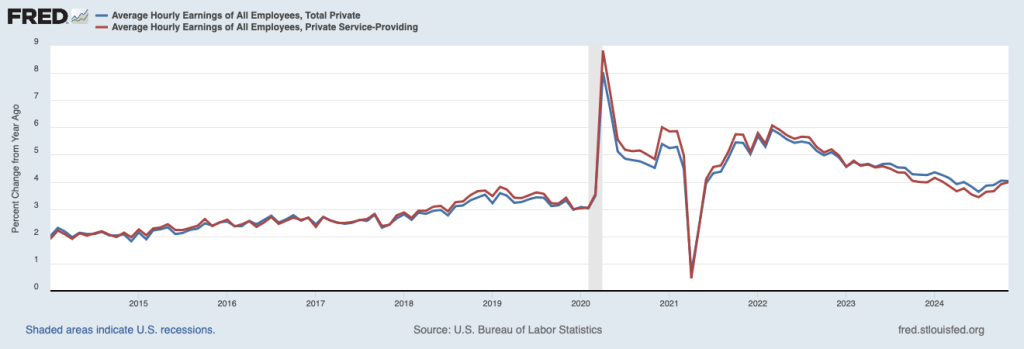

Furthermore, the most recent data on wages suggests that cost pressures coming from the labor market are no longer easing. The next chart shows twelve-month changes in average hourly earnings for all workers in the private sector (the blue line) and workers in the service-producing sector (the red line), where the discussion above indicates inflation momentum has been evident for some time. Growth in wages stopped slowing for both groups around mid-year and has been on a mild upturn since then.

Other evidence on the labor market largely supports the view that the labor market remains fairly tight. The rebound in employment in November from the storm- and strike-depressed level in October resulted in a 130 thousand average increase in employment in those two months. While down from the 190 thousand average monthly increase over the first nine months of this year, the October-November average moved closer to a pace that is sustainable over the longer run. The unemployment rate in November, 4.2 percent, also is close to the rate that is sustainable in the long run. (An increase in initial claims for unemployment insurance in the most recent week from the low levels of previous weeks is worth watching, but this series is quite volatile, especially around the holiday season.)

The above evidence on prices and wages indicates that it is difficult to wring out once higher inflation has become established. Various transitory factors — supply-chain problems, energy supply disruptions, and housing shortages — have largely washed out by now, but elevated inflation continues. This evidence points to a persistence in the inflation process that is not well understood and argues for considerable caution in pursuing further rate cuts. The evidence further suggests that the current degree of monetary restraint (which likely is less than many believe) may need to be applied longer than has been thought by market participants and many analysts.

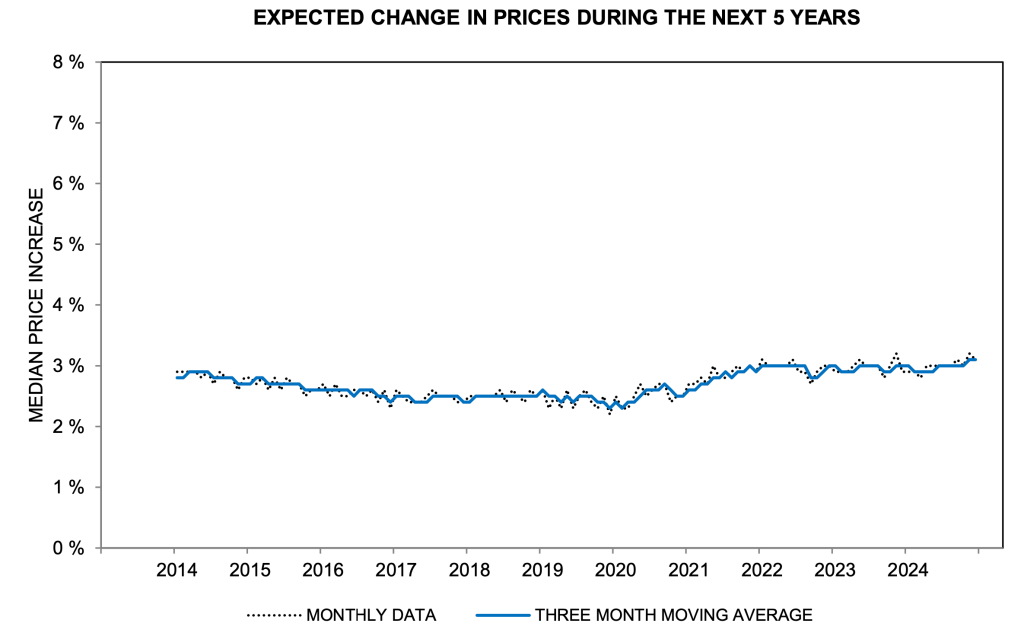

The inflation problem would have been much more serious at this point if the Fed had been less successful in convincing the public that it was serious about returning inflation to its 2 percent target. Repeated statements by Chair Powell and other policymakers about their determination to restore price stability, along with follow-up restrictive policy actions, have served to hold down inflation expectations. Shown below are expectations of inflation over the coming five years compiled from a survey of consumers conducted by the Survey Research Center affiliated with the University of Michigan.

These longer-term inflation expectations have been remarkably stable over the post-COVID period, when actual inflation has fluctuated considerably. However, they have remained somewhat above the pre-COVID period, further suggesting that the Fed’s job is not yet done.

Header Image: Scott Warman/Unsplash

Dr. Simpson.

I have enjoyed reading and studying some of your posts and in particular this one. It does a good job of explaining things in a way that most lay people should understand. That said, one concern of mine is that the added employment numbers I believe include an abnormal amount of government jobs added. Tell me if I am wrong on this, but also a concern is that particularly since Covid and the rampant inflation subsequently, I believe that many of the jobs added are counting people hit so hard by inflation that they have taken on second jobs. One can see the added people in second jobs changing in the fast food industry and in retail. A group that own many Whataburgers live here and tell me that the hiring age of their employees has reversed from what was average for many years. Now a larger percent of employees are older and much less of the percent of hires are young. Some of the older employees tell me that they retired, but no longer can get by on their retirement so took a menial job to fill in the gap. I have visited with several older employees in retail and I get the same story. Finally, if I understand your thesis on this subject, I agree that the Fed needs to hang onto the rates, if not raise them some to be sure the ugly head of inflation stays down for some time going forward. I enjoy working around you and we are surely blessed to have you here at this small university and in Kerrville! Prof. Kluting

LikeLike