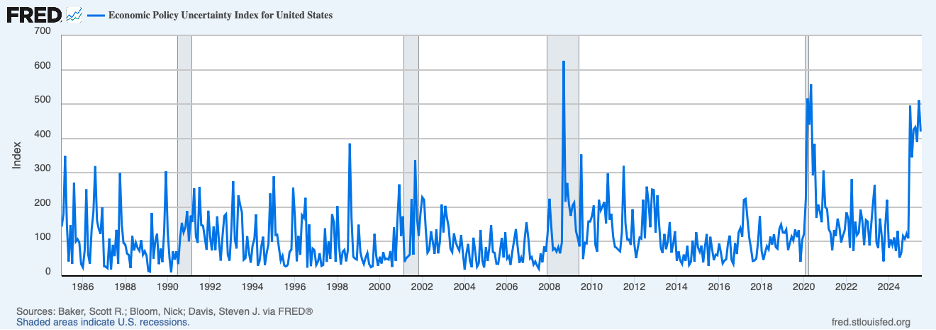

The Fed’s job of achieving the dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability has not gotten any easier of late. Tariff policy and intensified criticism of the Fed from the Administration is adding to policy uncertainty which, as shown in the chart below, is rivaling the periods of the financial crisis and the COVID shock. Outsized uncertainty is leading to business spending caution (acting to offset the positive effects of higher expected returns on investment coming from substantial deregulation).

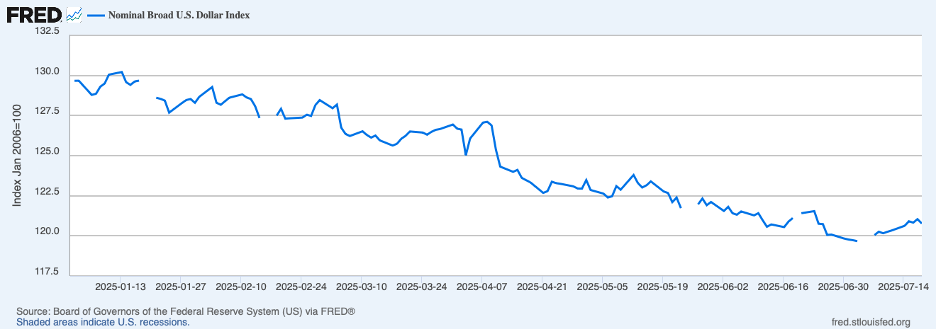

Concerns about the outlook for tariff levels and Fed independence are also weighing on the dollar, shown below, which has fallen more than 5 percent since the tariff surprise in early April.

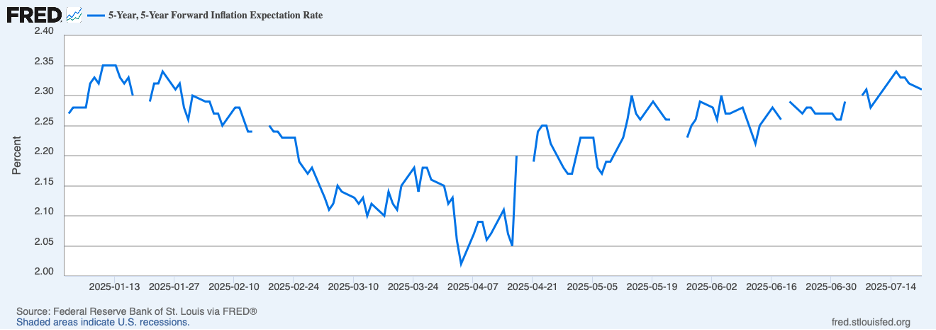

Furthermore, longer-term inflation expectations have moved higher since early April. This can be seen in the next chart showing expectations of inflation for the five-year period starting in five years derived from Treasury yields on nominal and inflation-protected securities. Indeed, this measure of longer-term inflation expectations turned up as pressure on the Fed intensified recently.

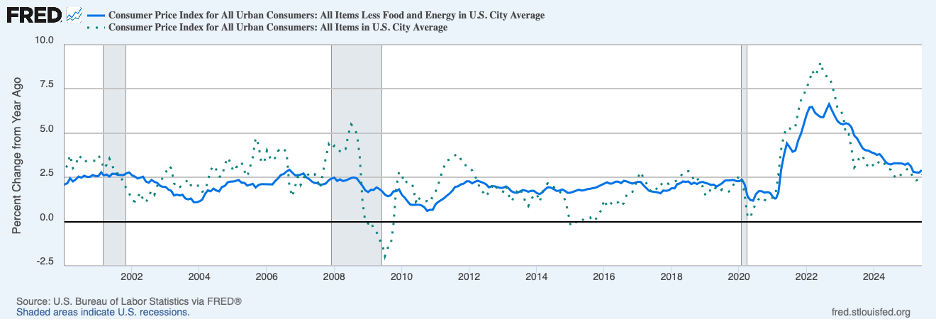

Turning to recent inflation news, the CPI for June, next chart, showed that tariffs were clearly affecting some categories of goods. The twelve-month increase in core consumer prices ticked higher to 2.9 percent in June from 2.8 percent in May while the twelve-month increase in headline prices rose to 2.7 percent from 2.4 percent (both were 0.3 percent lower than a year earlier). Notable increases (of 1 percent or more) were registered for computers, toys, sporting goods, appliances, video and audio products, window coverings and other linens, coffee, and spices — all of which have a high import content. (Early readings on corporate earnings for the second quarter are suggesting that business profits are also taking a hit from new tariffs, as some corporations are not passing through all of the higher costs from tariffs to consumer prices. If so, there is a question about whether businesses will continue to eat some of the costs from tariffs or will begin to pass more of those costs on to consumers.)

The next chart decomposes CPI inflation into twelve-month changes in prices of commodities excluding food and energy (the dotted green line), rent of shelter (the broken red line), and prices of services excluding rent of shelter (the solid blue line). Shelter-cost inflation slowed further in June, to a degree reflecting a sharp slowing in immigration, while prices of core commodities and services other than shelter accelerated again. The pickup in commodities owes importantly to new tariffs. More worrisome is the stubbornness of service-price inflation which continues to run a percentage point or more above the pre-COVID period.

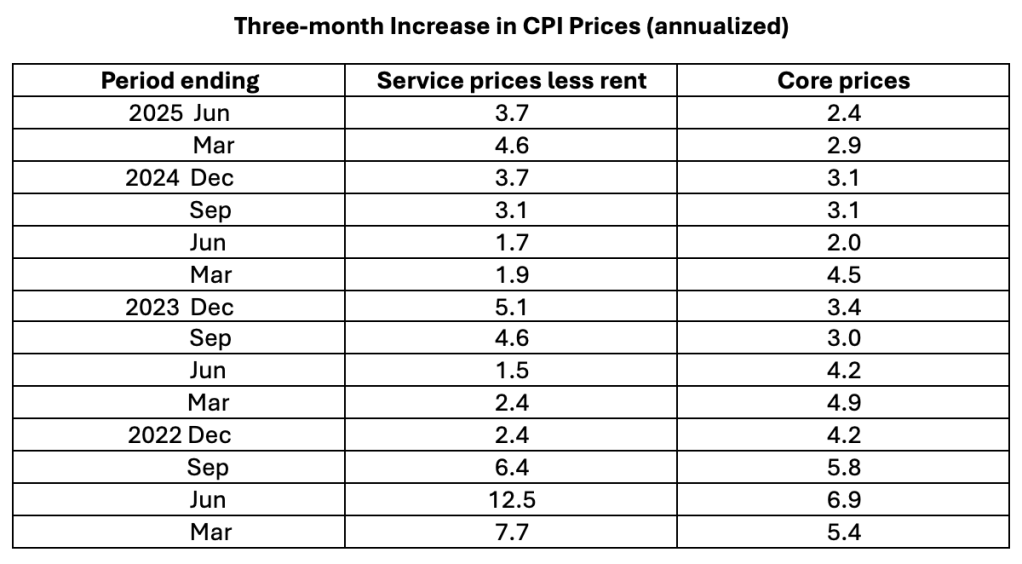

The table below showing annualized three-month changes in CPI service prices less rent of shelter (and core prices) can help to discern whether the trend in service prices may have slowed more recently. The table shows that inflation in service prices was actually higher over the three months ending in June than a year earlier, raising serious doubts about whether underlying inflation is slowing.

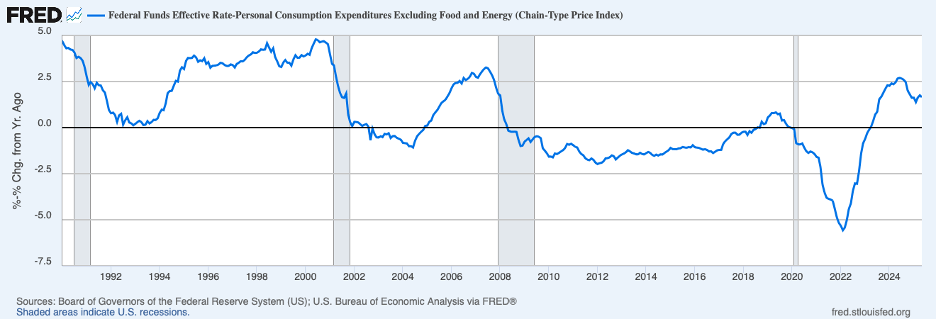

Lack of progress in lowering inflation along with an economy that is registering solid growth suggests that the monetary brakes are not being applied very hard for purposes of achieving price stability. The next chart shows the real federal funds rate (the effective nominal federal funds rate less the twelve-month percent change in core PCE prices) through May (the most current reading). This measure of the real federal funds rate, at roughly 1.7 percent, is not particularly high by the standards of the past few decades. (Of particular importance is the level of the real federal funds rate in relation to the real neutral federal funds rate — the rate at which Fed policy is neither stimulative nor restrictive. The neutral rate may be lower than a few decades ago, suggesting that Fed policy may be applying more restraint than comparisons with earlier periods might suggest; however, given the various economic forces that determine the neutral rate, the neutral rate likely is not a whole lot lower than earlier and thus Fed policy is not particularly restrictive.)

Acceding to pressures to lower the federal funds rate at this point is not the correct policy prescription if the Fed is to succeed in restoring price stability. Lowering rates at a time of still high inflation and solid growth would raise concerns about whether the Fed’s independence has been compromised, with the outcome being higher inflation in the future. Furthermore, higher tariffs and the drop in the dollar will, by themselves, be putting upward pressure on prices in the months ahead. Whether faster inflation will continue beyond the near term will depend on longer-term expectations of inflation. Uncalled for easing of policy at the present time will risk raising expectations of inflation and raising the odds that higher inflation is here to stay. The goals of sustained prosperity and a robust labor market will not be achieved in such an inflationary environment but will require price stability.

Header Image: Joshua Woroniecki/Unsplash