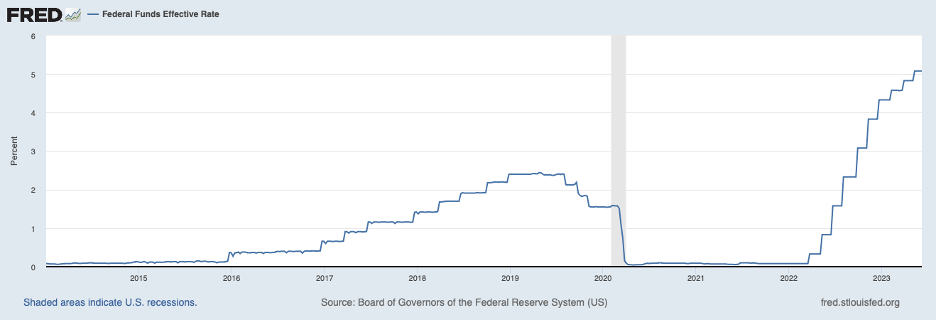

The issue: The Fed has sent out signals that it is inclined to pause rate hikes at its upcoming June meeting after successive increases over the past ten FOMC meetings dating back to March 2022 (see chart below). The cumulative increase in the target for the federal funds rate has been 500 basis points (100 basis points is 1 percentage point).

The rationale: The argument for a pause has been based on inevitable lags in effect of past interest rate increases and uncertainty about their ultimate impact. Once the full effect of past rate increases is realized, inflation could be on a downward trajectory toward the 2 percent target and perhaps a recession avoided. In addition, it is argued that the disturbance that hit the banking system in March with the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank has led to greater caution by bankers and they have responded by tightening lending standards and terms. This tightening will have a similar impact on the economy and inflation as additional federal funds target increases. In other words, the market has done some of the Fed’s work for it. A pause, it is argued, would give the Fed more time to assess the impact of past rate increases and the impact of the recent shock to the banking system.

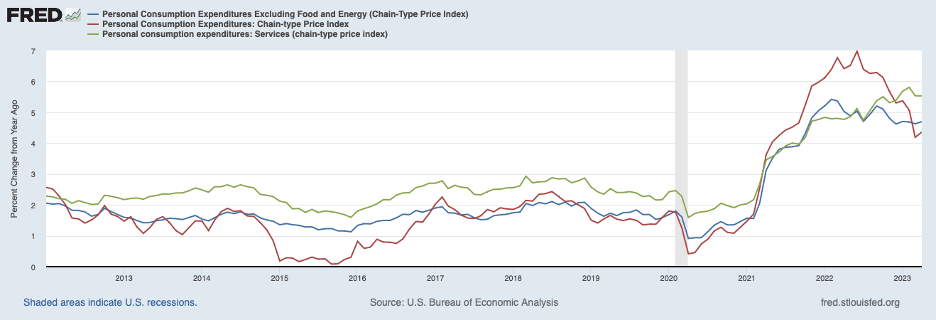

The evidence: Headline inflation, the red line in the chart below, is down more than two percentage points from the peak in mid-2022. However, core inflation—which excludes volatile food and energy prices, the blue line—has fallen by much less and has flattened out around 4-1/2 percent, well above the Fed’s 2 percent target.

Moreover, service price inflation, the green line, has been drifting upward over the past year and could be indicating that underlying inflation has become more entrenched. (Goods price inflation, not shown, has slowed a good bit over recent months, likely benefiting temporarily from an easing in supply chain pressures). Thus, it appears that underlying inflation has remained high and it is not the time to break the string of interest rate increases.

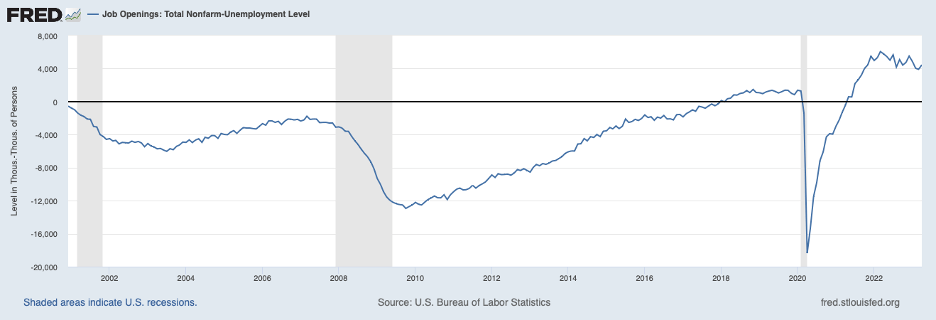

Consistent with stubborn inflation is the condition of the labor market. The next chart shows that the excess of job openings over the number of unemployed workers remains near its previous peak. Inflation is unlikely to be placed on a sustained downward path until there is slack in the labor market (a recession unfolds) and the chart below indicates that the job market has to cool off a good bit before slack emerges.

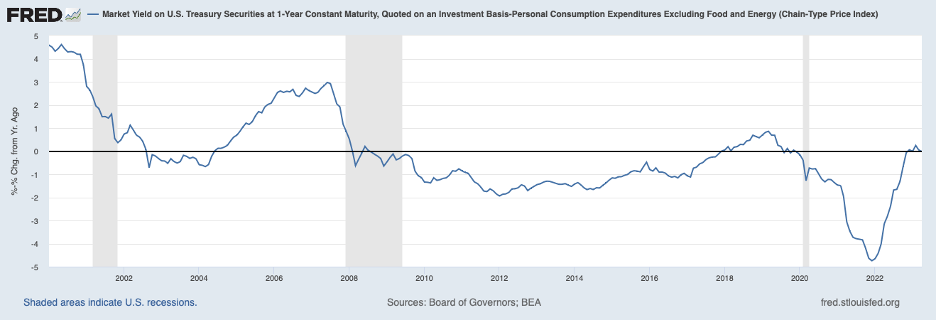

Real interest rates confirm that the Fed still has some distance to go in raising the federal funds rate before it begins to apply restraint on the economy and inflation. The next chart shows the nominal interest rate on a one-year Treasury bill less twelve-month core inflation. This measure shows that the real rate is only around zero, on the order of ½ to 1 percentage point below the neutral rate (the rate at which monetary policy is neither stimulative nor restrictive). To apply restraint against inflation, the real interest rate will need to be at least a full percentage point higher.

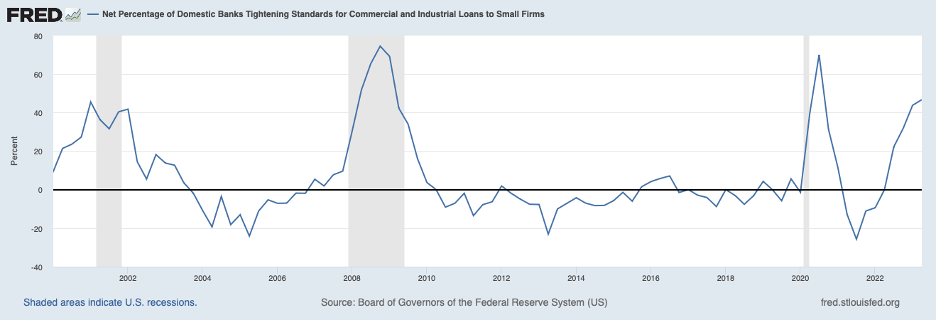

Turning to the restraint coming from bankers, the Fed’s own survey of underwriting standards at large commercial banks shows that, through early May, the degree of tightening of standards for loans to small firms slowed—did not intensify—after the March banking debacle, shown next.

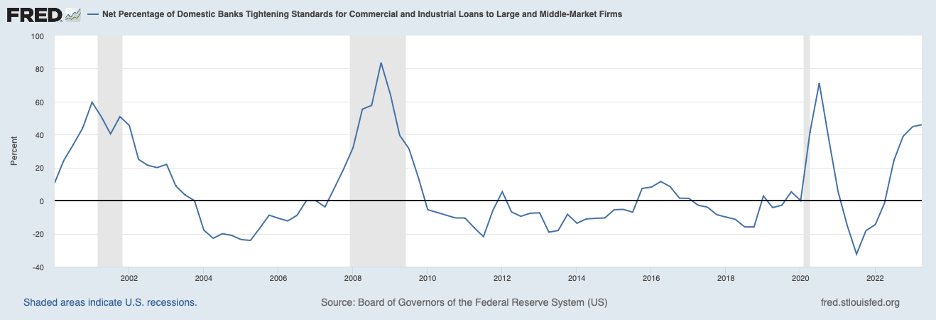

Moreover, standards for loans to large and middle-market firms, the next chart, were largely unchanged.

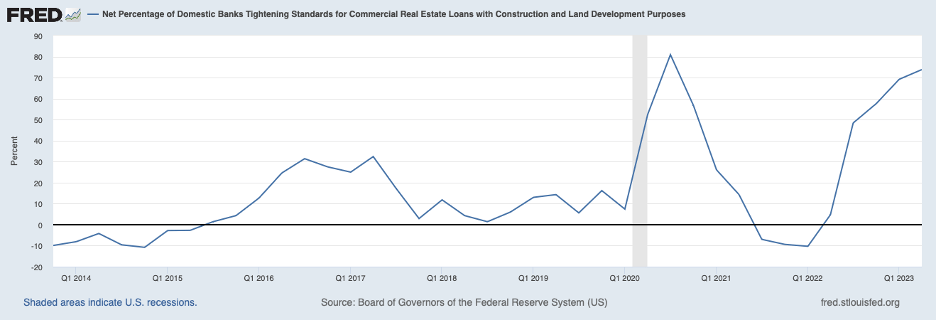

Even standards for loans to the commercial real estate construction sector, a sector that has become increasingly wobbly of late, barely tightened after the March disruption.

Thus, the evidence on lending standards clearly indicates that the degree of restraint coming from the banking system in response to the hiccup that occurred in March is fairly small and, by itself, doesn’t warrant a rate pause at this time.

Conclusion: The evidence shows that a rate pause at the current time would be premature. The Fed’s heavy-lifting job is not close to the end. The Fed needs to quickly move to the point at which monetary policy becomes sufficiently restrictive so that it places inflation on a distinct downward trajectory or the Fed risks inflation becoming even more entrenched. If inflation becomes more entrenched, the Fed’s job will become even harder—especially if inflation expectations ratchet higher. Furthermore, experience with previous periods of high inflation has shown that a dynamic develops in the inflation process that is poorly understood but makes inflation more intractable and the job of restoring price stability harder.