The focus of attention lately has been on the jump in long-term interest rates and whether this jump is doing the work of the Fed. What is behind the increase in long-term rates, and what does it mean for the Fed?

It is helpful to note that the long-term Treasury benchmark interest rate—most commonly the yield on the ten-year note—contains two separate components: an average of expected short-term rates (the federal funds rate) over the next ten years plus a risk premium that investors require as compensation for the price risk associated with holding a ten-year instrument.

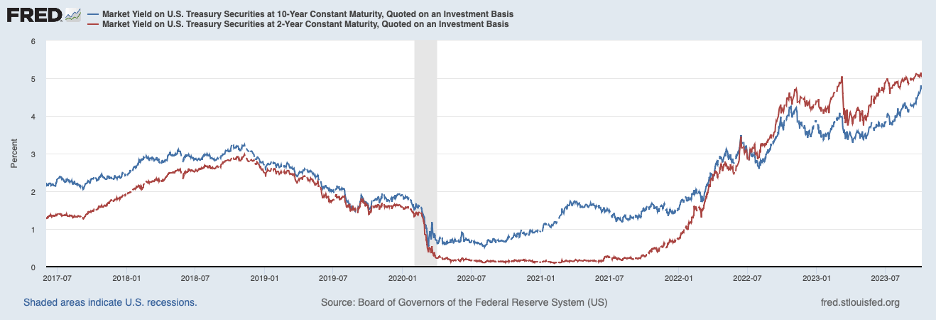

Below is the nominal yield on the ten-year Treasury note, the blue line. This yield has risen roughly 125 basis points (1.25 percentage points) since mid-May. The red line in the chart shows the yield on the two-year Treasury note, which has risen about 110 basis points over the same period. (Note: yields discussed in this report are through early October before the outbreak of war in Israel, which has led to a flight to safety and temporary declines in Treasury yields.)

Because the price risk associated with the two-year note is smaller and varies less than the premium on the ten-year note, a larger portion of the rise in the yield on the two-year note can be attributed to an upward revision to expectations for Fed policy for the federal funds rate (in effect, an upward revision to the outlook for aggregate demand by market participants).

If all of the increase in the two-year yield owed to an upward revision to the expected path of the federal funds rate over the next two years, this could account for only about one-fifth of the increase in the ten-year yield since mid-May. The implication is that the bulk of the increase in the ten-year nominal yield must be attributed to an increase in the term premium—investors want more compensation for holding longer-term Treasury debt. (A statistical model used to estimate term premiums attributes a smaller amount of the increase in the benchmark interest rate to the term premium.)

A growing chorus maintains that the upswing in the term premium indicates that investors in Treasury securities are becoming concerned about the unsustainability of the Treasury debt outlook and the ability of the United States to service its debt. In other words, the recent increase in longer-term Treasury securities largely reflects an increasing default risk premium.

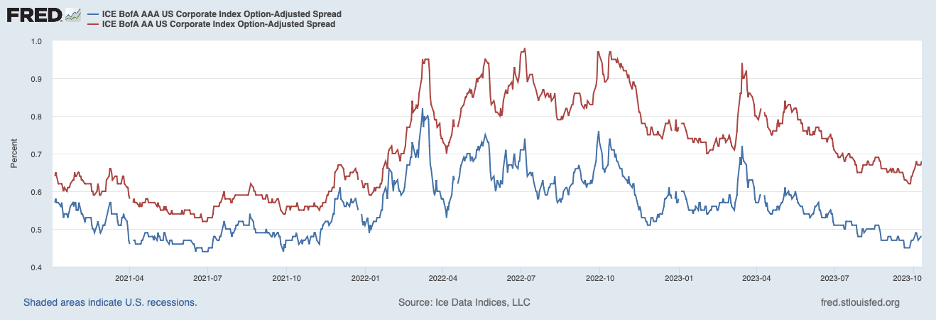

An implication of a perceived increase in default risk on Treasury debt is that Treasury yields would increase relative to those on high-grade other assets, such as top-quality corporate bonds. Shown next are yield spreads on AAA corporate bonds (blue line) and AA corporate bonds (red line). Both have narrowed about 10 basis points since mid-May, a relatively small amount but consistent with investors becoming more selective about Treasury debt.

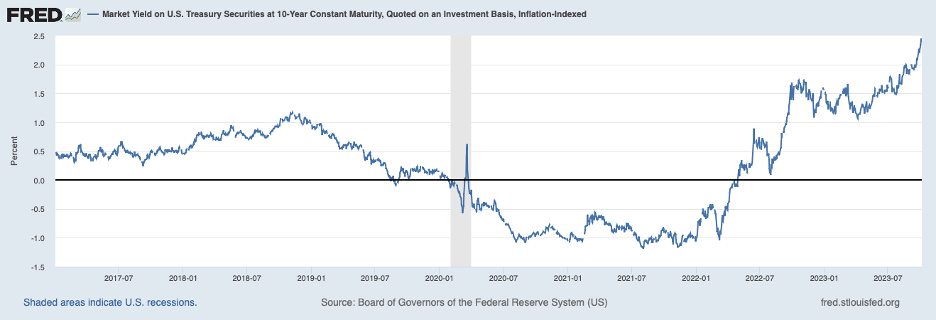

Of importance for monetary policy is the extent to which the increase in the nominal interest rate is accounted for by its real interest rate component. The real interest rate on the ten-year Treasury note is shown next. It has risen 110 basis points since mid-May—accounting for the bulk of the increase in the Treasury ten-year nominal interest rate—to a level of about 2.45 percent recently. No doubt, real interest rates at this level are imparting some restraint on the economy. (It is worth noting that an increase in the real interest rate faced by the Treasury that reflects a higher risk premium does not impose restraint on aggregate demand if higher risk premiums on Treasury debt do not affect other interest rates faced by borrowers.)

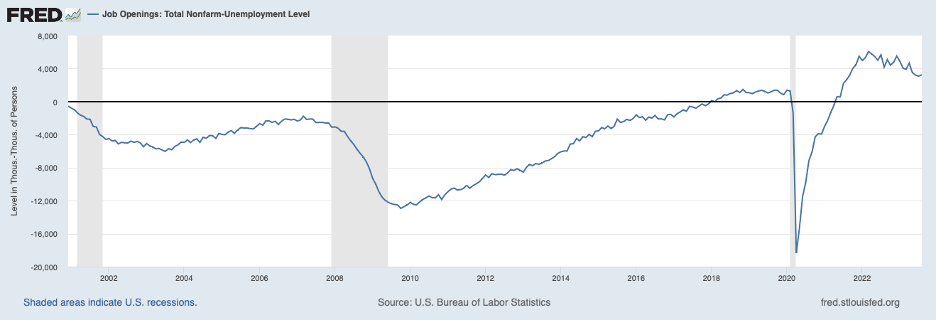

But is the restraint sufficient to place inflation on a downward path to the Fed’s 2 percent target? There are some indications that the economy will need an even higher real interest rate. Excess demand in the labor market, proxied by the excess of job openings over the number of unemployed persons in the chart below, has narrowed only slightly over recent months and still has some ground to cover before a more typical relationship is restored in the labor market. Moreover, new claims for unemployment insurance (not shown) have continued to run at historically low levels, confirming that the labor market stayed hot into early October.

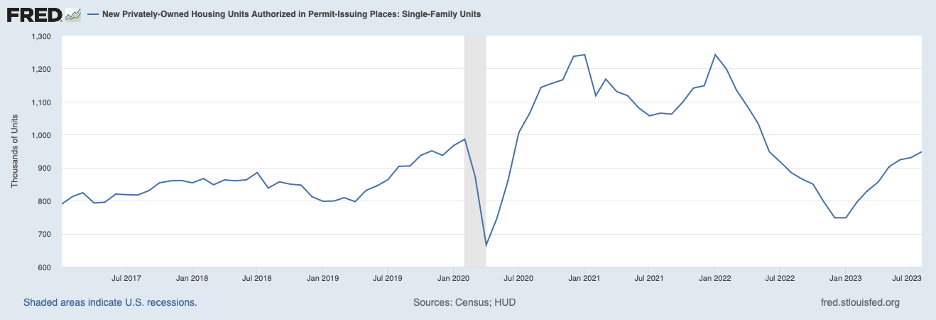

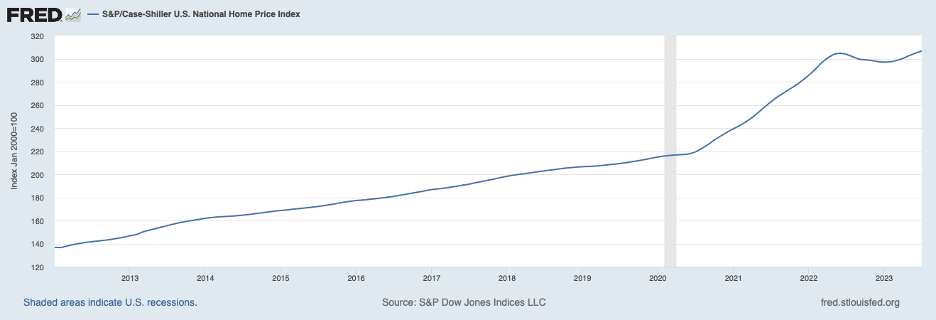

The housing market, which is one of the most responsive to interest rates, also hints that interest rates will need to rise further to sufficiently reign in aggregate demand to get to a path to price stability. The following chart shows that permits for single-family homes continued on the upswing through August (most recent data). The housing sector appeared to be weakening in response to the Fed’s tightening that began in early 2022 but has been on an upward march this year. Furthermore, prices for existing homes have also increased in 2023, as shown in the following chart.

Indeed, existing home prices rose at a 6.6 percent annual rate over the six months ending in July (most recent data), reflecting a resumption of strong demand for homes.

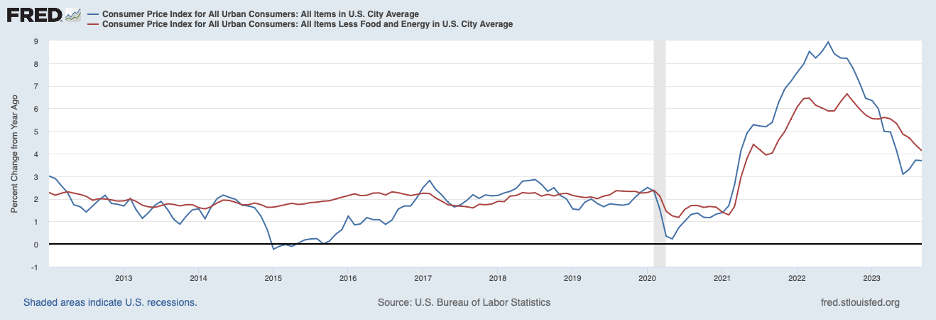

The most recent consumer price data also suggest that more monetary restraint may be needed. The following chart shows headline CPI inflation through September (the blue line) and core CPI inflation (the red line).

Headline inflation stayed at 3.7 percent on a twelve-month basis in September, boosted by further increases in energy prices, while core inflation slowed to 4.1 percent, still well above the Fed’s 2 percent target. Noteworthy is that the rise in core prices over the three-month period ending in September was 3.2 percent at an annual rate, below the twelve-month increase, perhaps suggesting deceleration.

Digging deeper, core inflation was held down by a further decline in commodity prices, still reflecting the unwinding of supply chain pressures. Once conditions in the market for commodities return to normal, commodity prices will stop falling and likely will begin rising. Moreover, prices of services excluding rent of shelter picked up to more than a 5 percent annual rate over the three months ending in September, well above the 2.8 percent twelve-month pace. In light of these disquieting developments, it would seem premature to celebrate victory in the battle against inflation.

In sum, the recent rise in long-term rates will help the Fed’s efforts to restore price stability. However, a few recent developments suggest that the long-term rate increase will likely not apply enough restraint to restore price stability. The Fed will need to raise its target for the federal funds rate further.

Any impending headwinds—such as firmer lending terms stemming from stiffer capital requirements on large banks and a resumption of repayments on student loans—may reduce the amount of additional Fed tightening needed but likely will not eliminate the need altogether. Perseverance is called for at this point to complete the job of getting back to price stability.