The April CPI numbers were in line with the expectations of market participants. This inflation news seemingly confirmed to market participants that underlying inflation is in the process of falling — after three consecutive months of unwelcome upside surprises. Moreover, other news on the economy was viewed as suggesting that growth has slowed, the labor market has moved into better balance, and a recession will be avoided — that is, a soft landing is on the horizon.

In response, there was a sigh of relief in financial markets as stock prices ascended to new highs and bond yields fell in keeping with renewed expectations that the Fed would lower its policy interest rate (the federal funds rate) by 50 basis points before year-end.

CPI Data

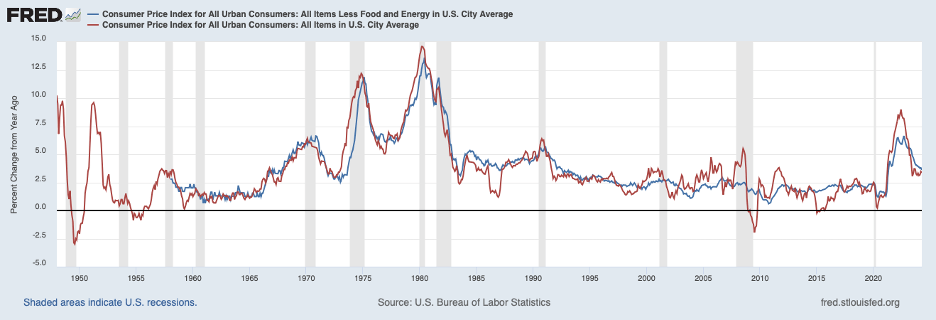

Does a careful reading of inflation and economic news justify such an optimistic outlook, or is this, again, wishful thinking? The headline CPI, shown by the red line in the chart below, rose 3.4 percent over the twelve months ending in April.

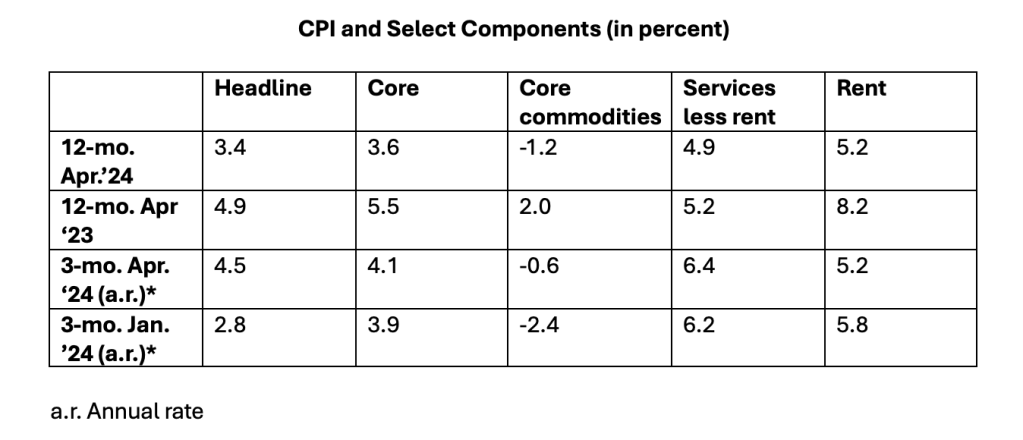

While this was 1.4 percentage points above the Fed’s 2 percent target for consumer price inflation, headline inflation in April was down 1.5 percentage points from a year earlier. Core inflation (which excludes volatile food and energy prices), the blue line, edged down to 3.6 percent in April, nearly two percentage points lower than a year earlier. The table below, though, shows that core inflation over the three months ending in April had picked up to a 4.1 percent annual rate, moving in the wrong direction.

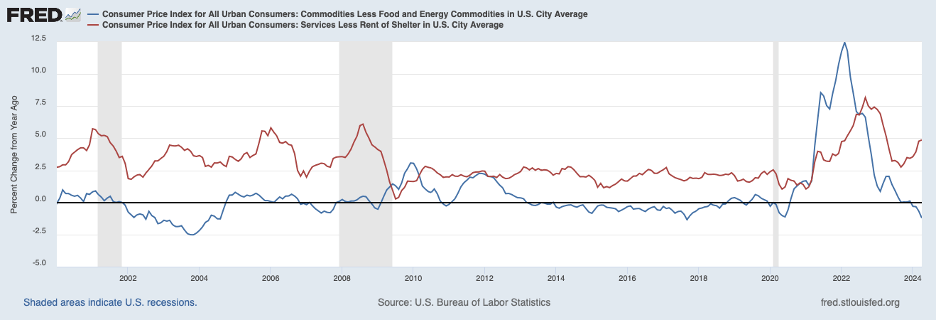

Digging deeper, the following chart shows core consumer commodity price inflation by the blue line. Due to supply-chain disruptions, core commodity price inflation has swung widely in recent years. Sizable declines in commodity prices had been holding down both headline and core inflation measures for several months. But judging from the -0.6 percent three-month core commodity rate of change for the period ending in April, the impact of supply chain disruptions seems to be largely behind us.

Service Prices

More concerning, though, has been the behavior of service prices. The red line above shows that inflation in service prices, excluding rent of shelter, has been moving upward on a twelve-month basis over recent months, reaching 4.9 percent in April. Moreover, the increase over the most recent three months was at a 6.4 percent rate, up from 6.2 percent over the previous three-month interval ending in January. Some have dismissed this acceleration in service prices by noting that the increases have been lumpy by components, such as auto insurance, and likely reflect one-off catchups. However, price changes by component tend to be somewhat irregular and not very smooth, even in times of persistent inflation.

Cost Pressures

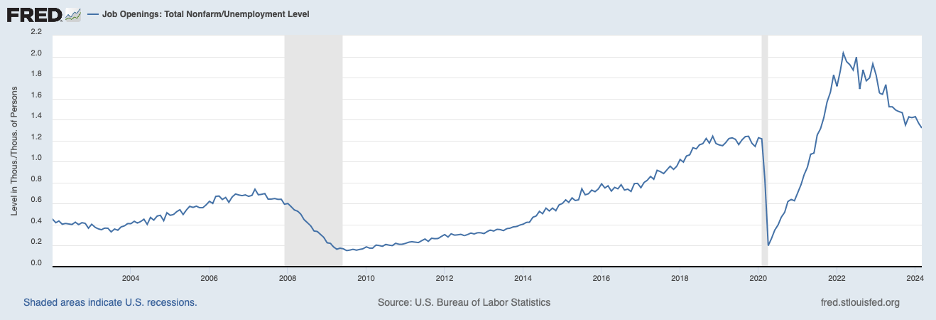

The following chart shows that the ratio of job openings to the number of unemployed persons has continued to drift downward and stood at 1.3 vacancies for each unemployed person in March (most recent data), down from around 2.0 a couple of years earlier. Nonetheless, this indicator points to a continued tight labor market as it remains well above the typical experience over the past couple of decades when labor costs and inflation were subdued.

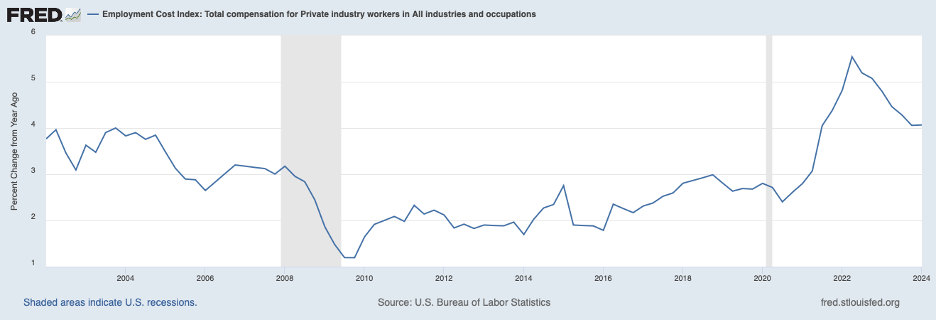

Tight labor markets put upward pressure on labor costs. The next chart shows that increases in labor compensation have largely tracked the degree of labor tightness upward and downward over recent decades. However, compensation growth leveled off at 4.1 percent on a twelve-month basis through March (more than a percentage point above the rate before COVID). And, over the most recent three months of that twelve-month period, compensation picked up to a 4.4 percent rate. Whether these data suggest that growth in labor costs has stopped moderating remains to be seen.

Slowing GDP

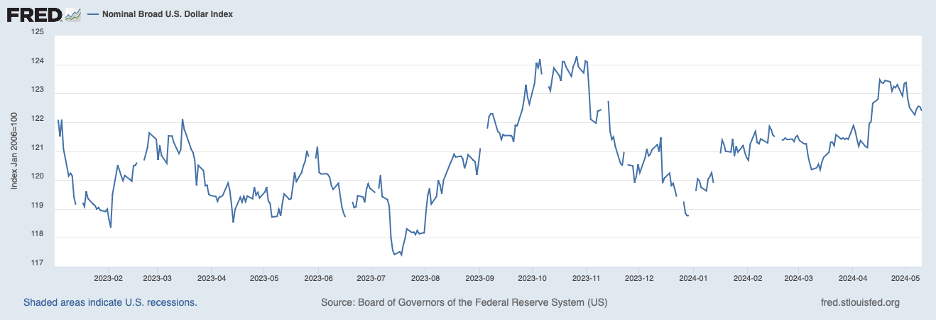

The slowing of growth in real GDP in the first quarter is likely not a sign that the economy has lost momentum, with implications for moderating inflation pressures, as some have concluded. Holding down growth in the first quarter were net exports, which, to a degree, reflected the strong dollar in the latter part of last year, shown in the chart below.

Much of that run-up in the value of the dollar has since been retraced, and the net export drag on growth is unlikely to be repeated in the near term. (It is worth noting that a stronger dollar tends to hold down inflation for a time and likely has kept consumer price inflation from being faster in recent months.) Also, a reduction in inventory investment trimmed growth in the first quarter, but generally, lean business inventory positions suggest that the need for businesses to restock will boost output growth and add to pressure on resources.

Indeed, early data on the second quarter point to a sizable pickup in growth in output.

Pulling Everything Together

The prospects for achieving the Fed’s two percent inflation target seem not as clear as many would like to believe. Even the celebrated April CPI data suggest that further deceleration in underlying inflation has stalled. Once inflation pressures become as persistent as they have been in the past couple of years, it takes a good bit of monetary restraint to make measurable progress in restoring price stability. Inflation is no longer an issue of secondary importance to businesses and consumers. For example, the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), in its most recent report for April, mentioned that cost pressures are the largest concern among smaller businesses. Moreover, consumers have been focused on price increases for some time and reportedly are changing their behavior to limit the sting of rising prices. In these circumstances, it takes more monetary restraint to curb inflation than what is implied by standard inflation models that capture inflation relationships during more normal times.

This reasoning suggests that Fed policy has not been restrictive enough. Clearly, any easing of policy in the months ahead would be ill-advised. Moreover, keeping the current policy position on hold may not be sufficient to place the inflation trajectory in a decidedly downward direction. Under current circumstances, the risks of easing too soon outweigh the risks of easing too late. Easing too late would lead to more unemployment temporarily while policymakers come to recognize the miss and act to correct it. Easing too soon could lead to an upturn in inflation that would become even more entrenched. Fixing that would require a considerably more restrictive monetary policy and more disruption to the economy and employment to break its back.

___

Featured Image: Reed Naliboff/Unsplash