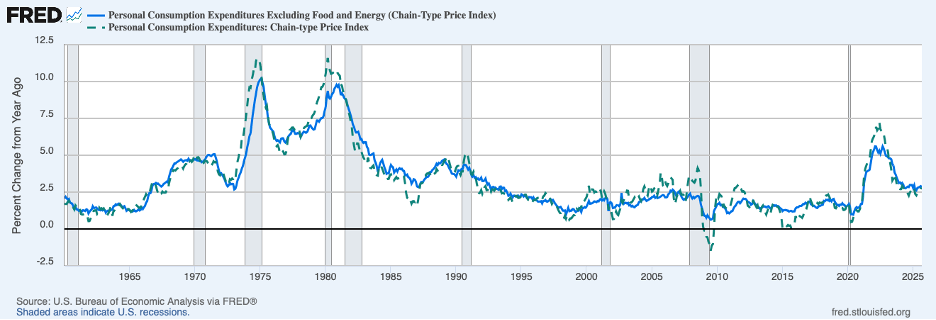

The Fed is of the view that inflation is receding toward its 2 percent target. The blue line in the chart below shows that core PCE inflation was 2.8 percent over the twelve months ending in September 2025 (latest data). Although this is the same rate of inflation as a year earlier, the Fed argues that inflation would have fallen in 2025 had it not been for the tariffs imposed during the year. In any event, inflation continues to run stubbornly above the rate that characterized the decade prior to the pandemic of 2020 (1.6 percent annual core PCE inflation) and the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus that the pandemic brought forth.

Meanwhile, the Fed has shown concern about a weakening jobs market since the summer of 2024. In response, it has lowered the target for the federal funds rate 1-3/4 percentage points since September 2024 to counter its perceptions of a deteriorating labor market.

According to Chair Powell, the last rate cut in December 2025 brought the target rate, “..within a range of plausible estimates of neutral…” In other words, the target for the federal funds rate of 3-1/2 to 3-3/4 percent was considered to be in the vicinity of neither a stimulative nor restrictive level.

For some time, the Fed has assessed the risk of a departure of employment from the goal to be on the side of a shortfall and the risk to inflation to be on the side of more inflation than the goal. Indeed, as noted, the Fed’s concern about the risks of a shortfall of employment has been behind recent rate cuts.

The Fed has a dilemma when inflation is high and employment weak or the risks on inflation are deemed to be on the upside and the risks on employment are deemed to be on the downside. Efforts to curb inflation by increasing the Fed’s policy interest rate will worsen the labor market while efforts to support employment by lowering the policy rate will worsen inflation.

The FOMC has addressed this issue in its Statement of Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy which it updates from time to time. The most recent version of the Statement was adopted August 2025, and reads:

The Committee’s employment and inflation objectives are generally complementary. However, if the Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it follows a balanced approach in promoting them, taking into account the extent of departures from its goals and the potentially different time horizons over which employment and inflation are projected to return to levels judged consistent with its mandate. The Committee recognizes that employment may at times run above real-time assessments of maximum employment without necessarily creating risks to price stability.

Note that the Statement mentions departures of employment and inflation from the FOMC’s objectives, implying that it will respond to inflation above or below target and employment below or above maximum (sustainable) employment. This treatment of inflation and employment is very similar to the wording of the Statement prior to 2020. However, the 2025 version has added the last sentence suggesting that employment may at times run above perceptions of maximum employment (an overshoot) without prompting a policy response.

The version of the Statement that prevailed from 2020 to the 2025 statement mentioned the following:

However, under circumstances in which the Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it takes into account the employment shortfalls and inflation deviations and the potentially different time horizons over which employment and inflation are projected to return to levels judged consistent with its mandate.

The wording regarding inflation is very similar, but the wording regarding employment indicates that the FOMC will respond to shortfalls of employment and not an overshoot. Thus, there is an asymmetric treatment of how the Fed responds to employment departures versus inflation departures in the 2020 version whereas inflation and employment departures are treated similarly in the 2025 version (apart from the last sentence of the statement).

Expressed differently, the 2020 version had a bias toward avoiding a shortfall in employment at the expense of the inflation goal. Indeed, research by two Fed economists indicates that this bias added nearly 1 percentage point to inflation compared with the symmetric response that characterized the period up to 2020 (Brent Bundick and Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau, “From Deviations to Shortfalls: The Effects of the FOMC’s New Employment Objective,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2026, 18(1): 69–101). At issue today is whether the latest version of the statement—2025—suggests that this bias has been fully removed. As noted, the 2025 version has very similar wording to the pre-2020 version, but has added the sentence, “The Committee recognizes that employment may at times run above real-time assessments of maximum employment without necessarily creating risks to price stability.” The addition of the employment sentence in the 2025 version implies that the bias towards maximum employment has not been fully removed.

None of the versions of the Statement acknowledges an important point when there is conflict between the employment and inflation goals: an established economic principle tells us that achieving sustainable maximum employment requires that inflation be in line with the inflation target (and with the public’s expectations of inflation). This principle seems to be recognized elsewhere in the 2025 Statement where it says:

Price stability is essential for a sound and stable economy and supports the well-being of all Americans.

This principle suggests that greater emphasis should be placed on the inflation objective when inflation is running above the 2 percent target. Moreover, there is a dynamic in the inflation process once inflation has taken hold, as it has since 2021, that results in more persistence in inflation than standard models of inflation have captured. All of this implies considerable caution in easing the policy interest rate until there is clear, convincing evidence that underlying inflation is on a distinct downward path to the goal.

The first chart above shows that the decades of the 1980s and the 1990s was generally a period of disinflation. Disinflation was achieved by the FOMC’s approach to monetary policy which came to be known as “opportunistic disinflation.” Under this approach, the Fed would respond more aggressively to a buildup of inflationary pressures than to a negative shock to output and employment—the result being a tilting of policy in the direction of disinflation. Opportunistic disinflation worked and the economy performed so well during this era—including achieving high levels of employment—that the period has since come to be labeled The Great Moderation.

Returning to employment, assessing the condition of the jobs market is especially difficult currently because of unusual crosscurrents affecting the labor market. First is the drastic slowing in growth of the labor force stemming from a dramatic swing in immigration policy. Prior to 2020, the growth in the labor force was on the order of 100 thousand per month. With the relaxation of border controls in 2021, that number swelled to 200 thousand or more. Over the past year, the number has fallen sharply, perhaps to 50 thousand per month. December job gains actually were 50 thousand, the same as the average monthly pace in 2025.

Complicating things further is an overstatement of employment in the monthly labor report. According to Chair Powell, this overstatement was on the order of 60 thousand per month for much of 2025. Whether the overstatement continued late in the year is unclear, but uncertainty about underlying growth in employment is exceptionally high.

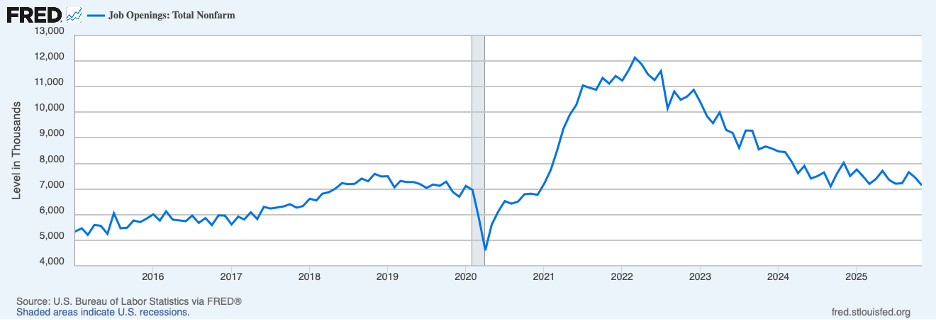

Second, productivity has taken a decisive upturn in recent quarters, likely the result of the surge in investment in artificial intelligence (AI). This upturn means that employers can produce output with fewer workers. (Preliminary data on hours worked in the fourth quarter of 2025 indicate that the number of hours worked was unchanged while output grew rapidly.) Employers seem to be dealing with these changing circumstances by posting fewer openings (the next chart, through November 2025). Nonetheless, the level of openings has been fairly stable over the past year and has not displayed much deterioration over recent months.

Furthermore, the level of initial claims for unemployment insurance (the next chart) has remained very low through the beginning of 2026, indicating that employers have not been discharging unusually large numbers of workers, despite headlines of big layoffs. (In addition, the unemployment rate for December in the monthly labor report—4.4 percent— remained in the narrow range that has prevailed since late summer.) In conclusion, it appears that the labor market has been remarkably stable in recent months despite being buffeted by extraordinary forces.

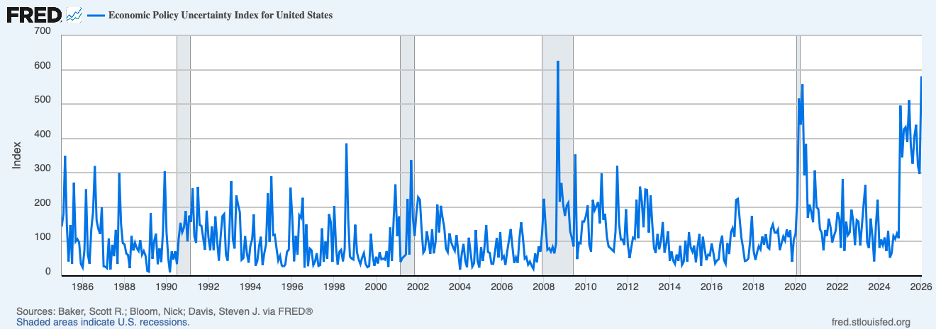

Meanwhile, the economy appears to have closed out 2025 on a strong note. Early estimates of growth of real GDP for the fourth quarter by the FRB Atlanta have the economy finishing the year at an even faster pace than in the brisk third quarter (5.4 percent in the fourth quarter versus 4.3 percent in the third). Such growth in the face of headwinds in the form of exceptional uncertainty about economic policy (the next chart) implies that monetary policy was not applying restraint on the economy and inflation in the second half of last year. Should it be a surprise that inflation remains stubbornly high?

In sum, the Fed appears to be continuing to put more emphasis on its employment mandate than its price stability mandate with the end result being a strong economy and continuing above-target inflation.

Header Image: Patrick Hendry / Unsplash