The high-profile closing of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) on March 9 and the subsequent closing of Signature Bank, the rescue package for First Republic, and the resolution of Credit Suisse have raised concerns about the health of regional commercial banks in the United States and certain big foreign names. Some have claimed that we are on the eve of another financial crisis on the order of 2008 while others view these banking problems to be isolated. So, which is it? Moreover, how are the disturbances likely to affect the course of monetary policy?

What the three U.S. problem banks listed above had in common were poor management and an appetite for risk. SVB, Signature, and First Republic had been identified by their primary regulators as having problems and the regulators had the tools to correct the problems but were tepid in addressing them. Notably, SVB had a high concentration of longer-term Treasury and federal agency mortgage-backed securities with values that were highly vulnerable to an increase in longer-term interest rates. SVB also had a very large share of its deposits that were uninsured and held by only a relatively few sharp-penciled depositors who were poised to withdraw their balances at the slightest hint of a problem at the bank. Indeed, the recognition by SVB depositors that SVB had experienced large losses on its bond portfolio led to prompt, massive outflows of deposits. Greater scrutiny was given by depositors of other regional banks that were feared to also be shaky and those banks experienced large deposit outflows, too. (Interestingly, some larger banks deemed by depositors to be sound were recipients of the funds withdrawn).

Federal authorities responded by announcing that the federal government would guarantee uninsured deposit balances at SVB and Signature Bank in an effort to stem the deposit outflows from these institutions. And the Fed assured banks that it stood ready to provide funding for banks experiencing losses of deposits.

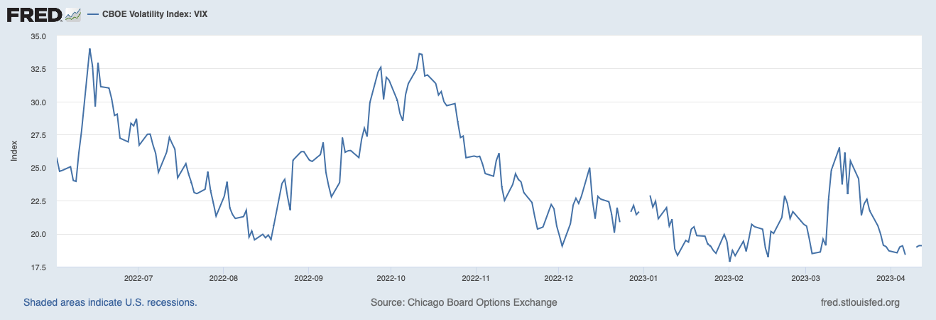

The drama over these banks and concern about wider-spread problems in the banking sector unsettled financial markets. As shown in the chart below depicting a market measure of prospective stock market volatility, uncertainty about prospective market volatility spiked in the wake of the SVB debacle, but not outside of recent experience. Moreover, prospective volatility retraced all of its earlier upward movement in the wake of measures taken by the federal government and by the absence of new difficulties emerging at other banks.

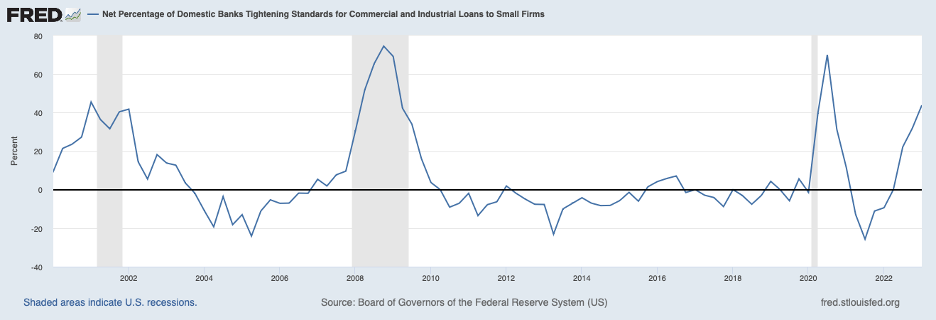

Nonetheless, the March banking disturbance likely has left an imprint in the form of more caution among banks. Commercial banks have been boosting their cash assets to better prepare for a loss of deposits and likely have also tightened their underwriting standards for making loans. The chart below shows the change in lending standards by larger banks for loans to smaller businesses through January of this year (most recent data). These banks had been tightening standards for small business loans prior to the March banking disruption (a similar pattern is displayed for loans by these banks to intermediate- and large-sized firms). In addition, banks may be reducing the amount that they lend to many of their customers and may be raising the rates that they charge (over and above benchmark interest rates).

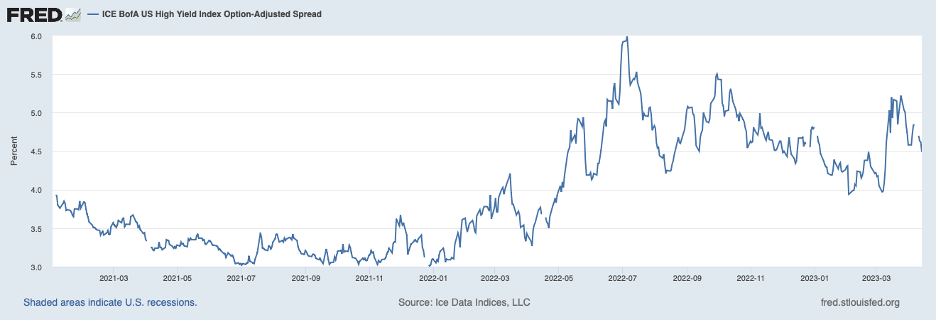

The next chart shows that in the corporate bond market the spread of the interest rate on below-investment grade bonds over the interest rate on Treasury securities rose appreciably around mid-March, but not above recent experience, and has shrunk a good bit more recently. A similar pattern likely was followed for rates on loans to below-investment grade borrowers at large banks.

The tightening of credit conditions at commercial banks has implications for monetary policy. Credit restraint at these banks is applying restraint on business and consumer spending in much the same way as increases in the Fed’s target for the federal funds rate. In other words, the tightening of credit conditions by commercial bankers is doing some of the work of the Fed in curbing inflation. Currently, the Fed is gathering information about what is happening in credit markets that will help it assess the extent to which credit conditions are being tightened. The update will include a new reading on the lending practices survey shown above.

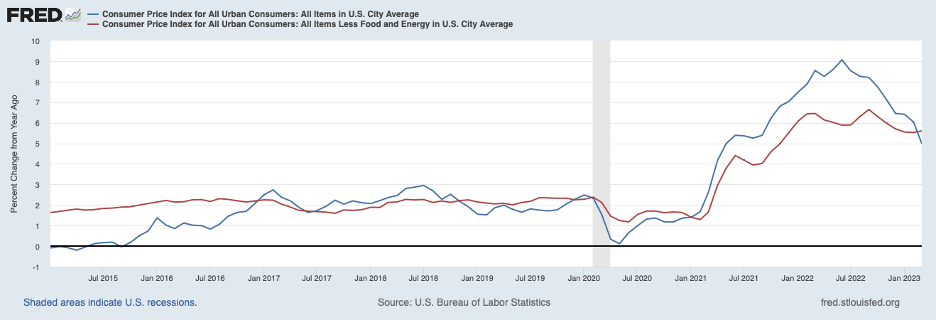

Meanwhile, the news on consumer prices suggests that inflation remains stubbornly high. The chart below plots the twelve-month percent change in the headline CPI (blue line) and in the core CPI (excluding food and energy prices, red line). Headline inflation cooled to 5 percent last month, largely owing to a temporary decline in energy prices (which has since been reversed). But core inflation stayed in the 5-1/2 percent area. Moreover, core inflation showed little evidence of fading over the three months ending in March.

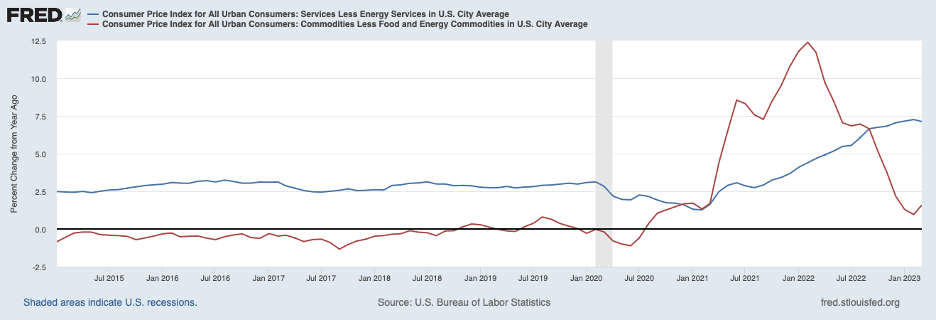

Breaking things down further, the decline in commodity price inflation appears to have come to an end as shown by the red line in the following chart. The ending of commodity price disinflation likely owes to the unwinding of supply-chain disruptions drawing to an end. More worrisome, service price inflation, likely more indicative of underlying inflation pressures, has not slowed and remains about 4 percentage points above its pace prior to 2021.

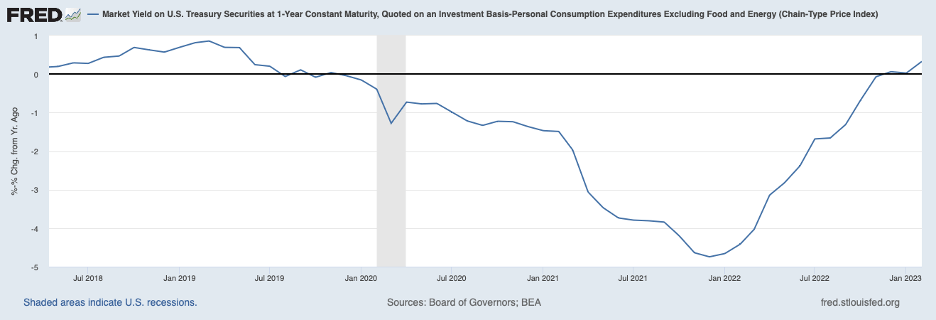

All of this indicates that the Fed still has work to do before the back of inflation is broken. The chart below has an estimate of the real one-year Treasury bill interest rate through February based on core PCE prices (the nominal one-year yield less the twelve-month change in core PCE prices). The real rate was barely positive in February (most recent data) and, even allowing for a tightening of loan markets in response to the banking disturbance in March, it is well below the level that will be necessary to curb inflation. The federal funds rate will still need to increase by at least another percentage point for inflation to be placed on a distinct and sustained downward trajectory.

The banking disturbance that unfolded in March appears to have been fairly isolated and is now contained. Nonetheless, the disturbance likely has led to more lending restraint by commercial bankers. There is a danger, however, that the Fed will overestimate the impact of the banking disruption on the credit process and restraint on the economy and inflation than what has actually happened. As a consequence, the Fed may be more tepid in raising the target for the federal funds rate than what is called for to achieve its stated objective of bringing inflation back to 2 percent. Financial markets are betting that the Fed will raise its target for the federal funds rate by only ¼ percent in early May and that will be the final tightening measure in this cycle. Should that prediction prove true, the inflation problem will not be licked but will require more stringent actions by the Fed down the road.